America's reverberating financial meltdown has Argentina's highly industrialized farming industry on the ropes. Until just a few months ago, farmers in Argentina — an agro powerhouse that exports to Europe and Asia's fast-growing markets — were thriving like never before. Now, the bottom has fallen out: They're struggling as demand plummets, and they say the Argentine government hasn't made it any easier.

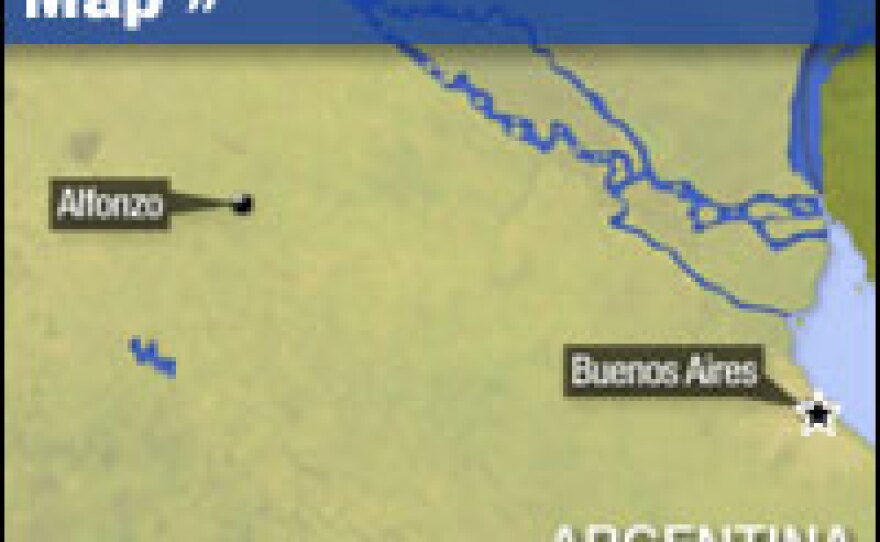

In tiny Alfonzo, population 1,100, what's being planted these days is despair about the future. A ferocious economic contraction has led to a 40 percent drop in key farm products like wheat and corn in just weeks.

After a planter spreads soybean seeds, row after tilled row, agronomist Walter Guillaunmet checks to see if there are 25 seeds per yard — as prescribed. Such attention to detail has made the cooperative of 900 farmers that Guillaunmet works for among Argentina's more prosperous.

But the historic high prices for soybeans — a grain used for everything from vegetable oil to animal feed — dropped almost overnight.

Nestor Jose Forti, 71, is among those feeling the pinch.

"There have always been highs and lows in Argentina, but a fall like this, I don't think I've ever seen," Forti says.

Farming Pressures Felt Away From Field

The local Argentine Club is where the people of Alfonzo gather. They go for weddings or to grill steaks, or just to have a beer and listen to an eclectic music collection.

Walter Martinez oversees the club, which is supported by Alfonzo residents. He says the club has been expanding.

The renovations attest to recent good times. Martinez explains that when farming does well, so does the club. He likens the boom-bust of farming to the rains, which come with fury across the flat pampa, and then disappear for weeks on end.

"It rains — the club fills with people," Martinez says. "Doesn't rain — the spirit in the club falls."

Much Like Iowa

Now, Martinez says, the pampa is going through a prolonged dry spell. On the surface, however, this fertile region doesn't easily reveal its ills.

The farming communities feature well-kept homes and nondescript storefronts. Windmills dot the landscape, along with silos and billboards for John Deere tractors. It could easily be mistaken for Iowa.

Farmer Hector Farroni has, in fact, been to Iowa — he took his new bride there soon after they married, just to take a look. The home he shares with his family — and the farm animals — is bucolic: wheat, soy, cattle and corn cover 500 acres.

As in Iowa, this farm's muscle is grain. It's harvested and pumped onto trucks, then shipped to the rest of the world.

Farroni's ancestors came here from Italy, like many families in Alfonzo. A century ago, they helped make Argentina one of the world's richest countries.

More recently, in 2002, farmers helped pull Argentina out of the last of many economic crises that have buffeted the country.

Signs Of Trouble

But Farroni says the reality now is that the worldwide crisis is hammering farmers. He says the cost of fertilizers, herbicides and other necessities has gone up at the same time. He says the only card farmers now have is to just remain hopeful.

The first signs of trouble came earlier this year, when rising taxes prompted farmers to protest by the thousands. The farmers charge that Argentina's leftist government has an anti-farmer stance.

Congressman Hector Recalde is a strong supporter of President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner's policies. He says a robust domestic market coupled with worldwide demand for Argentine products ensure prosperity on the country's farms.

"There will always be demand for what we produce, unless the world stops being hungry," Recalde says.

But farmers in Alfonzo charge that Fernandez de Kirchner is looking to do what other Argentine governments have done — redistribute wealth on the back of the farming sector.

Forti, who because of his age is among the most respected farmers in Alfonzo, says the government is intent on sapping the region of its wealth. The government says it wants to redistribute wealth, he says, but what is being distributed is poverty.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))