The search for the perfect artificial heart seems never-ending. After decades of trial and error, surgeons remain stymied in their quest for a machine that does not wear out, break down or cause clots and infections.

But Dr. Billy Cohn and Dr. Bud Frazier at the Texas Heart Institute say they have developed a machine that could avoid all that with simple whirling rotors — which means people may soon get a heart that has no beat.

Inside the institute's animal research laboratory is an 8-month-old calf with a soft brown coat named Abigail. Cohn and Frazier removed Abigail's heart and replaced it with two centrifugal pumps.

"If you listened to her chest with a stethoscope, you wouldn't hear a heartbeat," says Cohn. "If you examined her arteries, there's no pulse. If you hooked her up to an EKG, she'd be flat-lined."

The pumps spin Abigail's blood and move it through her body.

"By every metric we have to analyze patients, she's not living," Cohn says. "But here you can see she's a vigorous, happy, playful calf licking my hand."

Human Trials

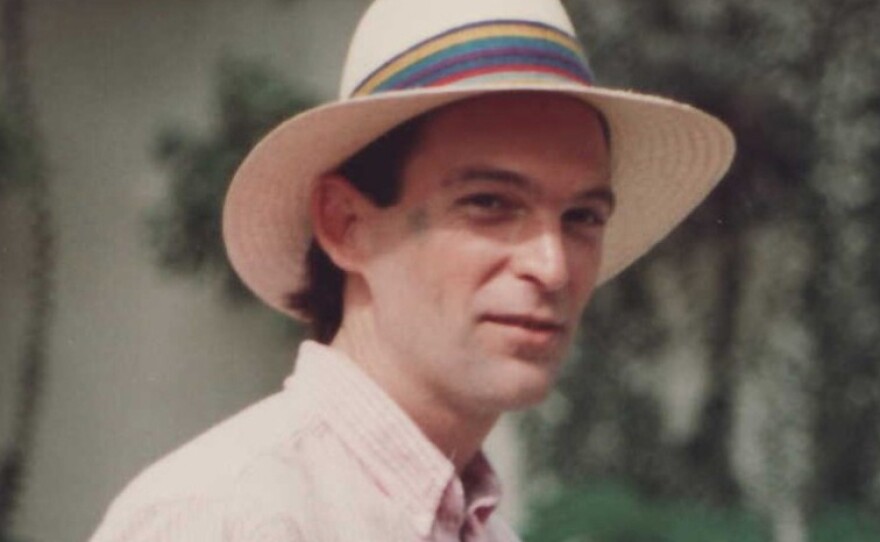

In March, after practicing on 38 calves, Cohn and Frazier felt confident enough to try their device on a human patient. They chose Craig Lewis, a 55-year-old who was dying from amyloidosis, which causes a buildup of abnormal proteins. The proteins clog the organs so much that they stop working.

In Lewis' case, his heart became so damaged, doctors said he had about 12 hours left to live.

His wife, Linda, said they should try the artificial heart.

"He wanted to live, and we didn't want to lose him," she says. "You never know how much time you have, but it was worth it."

Lewis worked for the city of Houston, helping to maintain the city's vast system of wastewater pumps.

At home, in his garage, Lewis dabbled in woodworking, metalsmithing and what his wife calls general "piddling around."

"He would go into his shop and create or fix or modify something to make it work," she says.

That's what his two doctors did, too. Linda Lewis says her husband appreciated how the doctors cobbled together the pulseless heart from various materials.

"Dacron on the inside and fiberglass impregnated in silicone on the outside," Cohn says. "There's a moderate amount of homemade stuff on here."

Cohn and Frazier did not start totally from scratch. They took two medical implants known as ventricular assist devices and hooked them together.

A ventricular assist device has a screwlike rotor of blades, which pushes the blood forward in a continuous flow.

Thousands of people have one of these implanted close to their hearts, including former Vice President Dick Cheney. By using two, the doctors replaced both the right and left ventricles — the entire heart.

"I listened and it was a hum, which is amazing. He didn't have a pulse."

"I listened and it was a hum, which was amazing," Linda Lewis says. "He didn't have a pulse."

The doctors say the continuous-flow pump should last longer than other artificial hearts and cause fewer problems. That's because each side has just one moving part: the constantly whirling rotor.

But Cohn says they will still have to convince the world that you don't need a pulse to live.

"We look at all the animals, insects, fish, reptiles and certainly all mammals, and see a pulsatile circulation," he says. "And so all the early research and all the early efforts were directed at making pulsatile pumps."

However, the only reason blood must be pumped rhythmically instead of continuously is the heart tissue itself.

"The pulsatility of the flow is essential for the heart, because it can only get nourishment in between heartbeats," Cohn says. "If you remove that from the system, none of the other organs seem to care much."

Progress and Setbacks

After the implant, Craig Lewis woke up and recovered somewhat. He could speak and sit up in a chair.

But then he began to fade as the disease attacked his liver and kidneys.

"Amyloidosis is horrible," Linda Lewis says. "I could see the other organs were not cooperating."

Craig Lewis lived for more than a month with the pulseless heart. He died in April, due to the underlying disease. His doctors say the pumps themselves worked flawlessly.

"We knew if it wasn't a success for Craig, if they could get data that would help them, if it helps the next person, then you did good," Linda Lewis says.

Biomedical companies worldwide are still trying to perfect a pulsing artificial heart.

But Cohn says those companies are like the last buggy-whip manufacturers: fine-tuning a product that will soon become obsolete.

He is sympathetic to their efforts, though. He points out that the history of invention is full of dead ends.

"When man first tried to come up with machines that flew, he looked around and saw bats and birds and butterflies and mosquitoes," Cohn says. "Everything had wings that flapped."

But what works in nature is often not the only mechanical solution, or even the best one.

"When they saw that you could create wind, and that wind over a fixed wing was a great way to provide lift, then the whole field shifted," Cohn says. "There are very few flying machines in modern times that have flapping wings. And I think this is the same intellectual leap in pumping blood or pumping fluids."

In order to bring a continuous-flow artificial heart to the market, the doctors will have to decide on a final design, find a manufacturer and get FDA approval.

Although there's more work to be done, Frazier says he's confident the pulseless approach will win out in the end.

"These pumps don't wear out," he says. "We haven't pumped one to failure to date."

The tradeoff, of course, is the loss of the familiar, primordial sound of a beating human heart. For these surgeons, though, that's a small, poetic price to pay to make medical history.

Copyright 2022 Houston Public Media News 88.7. To see more, visit Houston Public Media News 88.7. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))