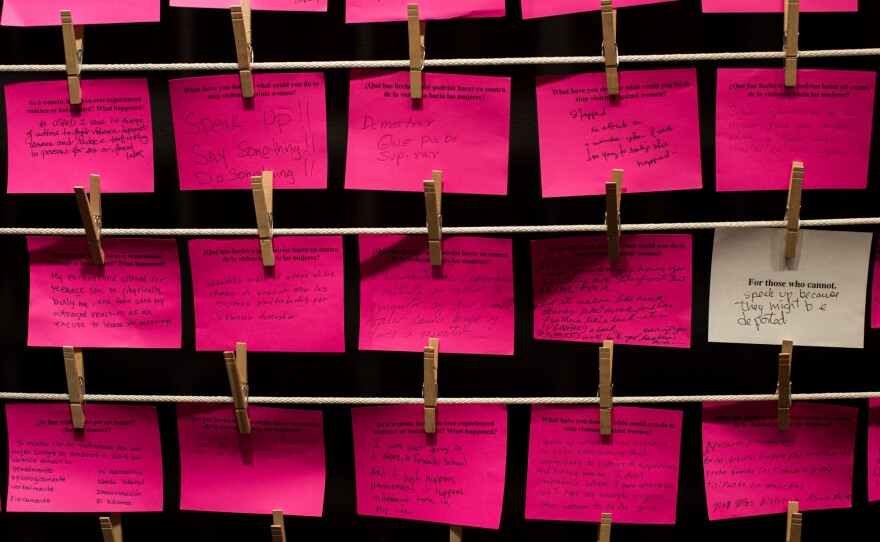

Pink rectangles of paper, pinned to rows of clotheslines, festoon a gallery wall at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. Each slip bears a note, handwritten by a museum visitor, that answers a question about sexual harassment and violence.

"As a child in a museum I was flashed, as a teen in the university library I was groped, as a student at the college doctor, again I was groped. No place is safe. But each time I felt I had to be polite. Not next time!" reads one.

The messages are part of Mexican artist Mónica Mayer's piece "El Tendedero/The Clothesline Project." "El tendedero" is Spanish for "the clothesline," and the entire exhibit is in English and Spanish.

Mayer has done more than 30 variations of the piece. The goal: to visualize harassment of and violence against women.

It all started in 1978, when Mexico City's Museo de Arte Moderno asked young artists to create pieces around the theme "The City." Mayer chose to address how she felt in the city as a woman. "I was already a feminist and a feminist artist," she recalls. "So I decided to go toward what was important to me, which was public harassment and how much I disliked harassment in public transport."

So she asked women of all ages, professions and social classes what they disliked about Mexico City. "The first reaction was to complain about other things," Mayer says. "But the piece is not a survey but a way of raising consciousness, particularly 40 years ago. So, when they said they disliked the traffic, I would ask them if they didn't dislike being harassed." She put 800 of their answers on a clothesline as an installation piece.

Mayer says she had been harassed as a child and didn't realize it was such a common experience. The project became, in a way, an act of self-defense. "Back then, it's like a prehistoric #MeToo, because there was no awareness about sexual harassment or very little," she says.

For the D.C. exhibition, open until January 5, the questions were developed in collaboration with local artists and activists, women from a D.C. shelter and a Latino-focused health clinic. The prompts include: "As a woman, where do you feel safe? Why?" and "What have you done or what could you do to stop violence against women?"

Mayer has staged the project to Mexico, Colombia and the U.S., and she says gender-based harassment is equally salient in all three.

In some ways, things haven't changed since Mayer started "El Tendedero" in 1978, she says. UN Women reports that 14 percent of women in Mexico will experience physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner in their lifetime. In 2014, Mexico City was ranked as having the second-most dangerous transit system for women of the world's 15 largest capital cities. That's according to a survey by Thomson Reuters Foundation News that asked women about their experiences on public transportation.

But now, more people are talking about violence and harassment, Mayer says: "I think we're becoming more aware as a society."

Harvard doctoral student Paola Abril Campos, who focuses on reproductive health, sexual health and reproductive justice, agrees. Campos grew up in Mexico City. After living abroad and returning home, she realized how street harassment disrupted her daily life. In 2012, she studied Mexico City street harassment, concluding that two thirds of the 952 women she surveyed had experienced street harassment the month before.

Campos thinks art pieces like Mayer's can help take on the issue. "I think it's hopefully putting the topic on the table and sparking discussion and hopefully changing the way people see these problems," she says.

Claudia Díaz, director of biomedical and public health research at the Population Council's Mexico office, worked with Campos on that research. "Projects like this clothesline are relatable," she says.

The solution to everyday violence — on public transit or anywhere else — may not be complicated. Mayer says, "If 70 percent of the people in the bus did something when they saw something, it wouldn't happen anymore," she says.

"I think harassment will end when, as women, we don't take it and we react against it, and as men become more aware of how they were brought up to think this is acceptable," Mayer says. "And as a society we don't accept it."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))