Let's see — what shall we have? So much to choose from in the collection of historical menus at the Los Angeles Public Library.

There are some 9,000 items to consider — creative, colorful, delicious-looking. By just perusing the choices we get a deep sense of the city's rich culture and juicy past.

The options are opulent. The Library Foundation has mounted a multiplatform exploration of the menu collection, including an exhibit of menu-rabilia titled To Live and Dine in L.A.: Menus and the Making of the Modern City, and a companion book written by Josh Kun, a communication professor at the University of Southern California.

Working for more than a year, Kun and a stew of students — with guidance from Los Angeles chef Roy Choi — culled through the culinary relics. They mulled over the many, many menus to uncover stories of the people of Los Angeles — by looking at what they ate, what they paid, where they dined.

The settling of the American West, the city's growing diversity, the rise of Hollywood, the country's digital makeover and more are all reflected in the menus of Los Angeles. Plus, they occasionally portend some historically good food.

Maybe we will just sample a sampling, a soupcon of the menus that will give us a sense of L.A. long ago — and why the city is the way it is today. What would you recommend? we ask Josh Kun. He serves up a trio of delectable — and meaning-filled — finds:

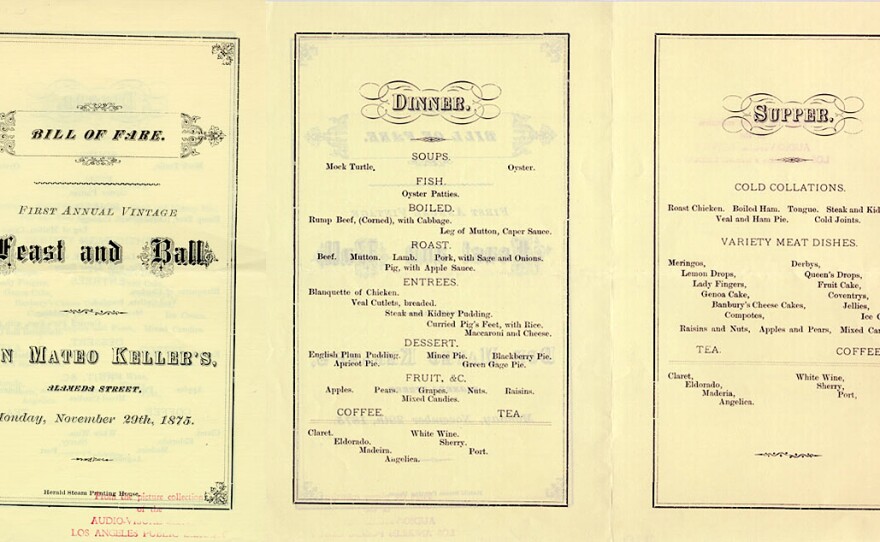

Don Mateo Keller (1870s)

This is the oldest menu in the Los Angeles Public Library's collection, Kun tells us, dating back to 1875. It is a Bill of Fare for the first annual Vintage Feast and Ball held at Don Mateo Keller's own 10-acre vineyard. An Irish immigrant, Keller "was a successful vintner with tremendous real estate luck," Kun says. "He bought up the original land grant for a stretch of terrain called Malibu."

In 1875, Keller's wine-making enterprise was booming. The Los Angeles Herald of July 11 reported that the vintner had ordered 18,000 white oak staves and a large amount of new oak barrels. "All this betokens great activity in the Los Angeles wine trade," the paper noted.

Keller's 1875 private invitation feast, Kun says, "lasted all day and included both 'dinner' and 'supper' servings." It was a carnival for the carnivore, offering cattle and sheep and pig cooked various ways.

Van's Louisiana Barbecue (1940s)

In 1942, war-time food rationing was in full force. The Southern California Restaurant Association, the Associated Press reported on April 30, warned that all-you-can-sweet sugar bowls might soon disappear from area cafes and waitstaff would be instructed to administer one teaspoon or cube of sugar for each cup of coffee or bowl of cereal.

The menu from Van's Louisiana Barbecue, Kun tells us, included a reprint of a Daily News story explaining to customers that the Restaurant Association had also called for an end to 'special dinner combinations' — to further eliminate food waste during rationing.

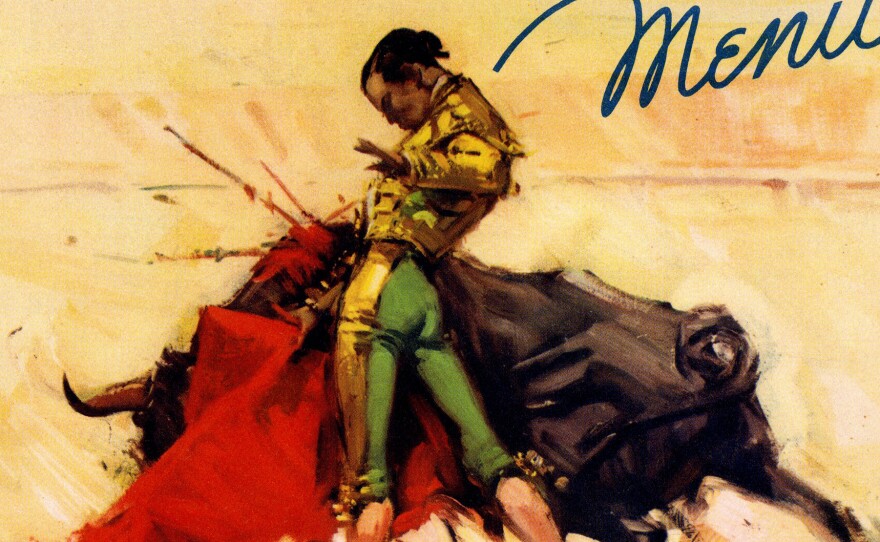

"That the restaurant probably catered to the neighborhood's growing African-American community and that the menu was printed on a stock advertising menu card for Mexican brewery Carta Blanca with a watercolor of a Mexican bullfight on its cover," Kun says, didn't prevent Van's from expressing anti-Japanese sentiments during the war on its menus. "It's just one example of what L.A. menus can tell us about food's connection to larger social and cultural forces, the way social entrees like class, race and gender shape the way the city eats and the way it thinks."

Ma Maison (1970s)

The romantic role of L.A. restaurants — such as Ma Maison and Spago — as after-hours rehearsal studios continued into the 1970s and 1980s. A new generation of A-list actors practiced lines and played out scenes in corner booths, says Josh Kun.

Meanwhile, there was a "California cuisine" revolution in the kitchens. "Out with sauté stations and in with grills," Kun says. "Replace old-school Continental cuisine with new-school 'local' and 'regional' and turn all things 'haute' into comfort food, served ... in a restored breezy beach bungalow with an open kitchen."

Menus, he says, "were the revolution's manifestos, and they were changed daily. Shifts in food politics and food tastes were accompanied by the rise of desktop publishing, so menus no longer had to be formally printed and delivered to restaurants but could be written, designed, and modified all in-house and on the fly — even in the middle of a meal when the kitchen runs out of sea urchin or shredded pickled ginger."

Mediography

"Exploring the Los Angeles Public Library Menu Collection". LA Weekly, Sept. 26, 2012

"L.A. Library Foundation Launches 'To Live and Dine in L..A' Menu Project", Los Angeles magazine, Aug. 20, 2014

"Roy Choi and Josh Kun on food, politics and L.A. history", Los Angeles Times, April 19, 2015

Follow me @NPRHistoryDept; lead me by writing lweeks@npr.org

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.