Editor's note: This is the third in a four-part series. Here are parts one, two and four.

A dusty human skull, a spine attached to leg bones clothed in pants, and an arm bone pose a mystery: do these belong to Marco Antonio Garcia, a 20-year-old missing Mexican migrant?

Gregory Hess, Pima County’s chief medical examiner, knows this person probably died crossing the U.S.-Mexico border through the Arizona desert. A group of volunteers called Aguilas del Desierto, or Eagles of the Desert, found the remains about 10 miles north of the border during a search for Garcia.

The group — plumbers, construction workers and farmers who search for dead or dying migrants at the U.S-Mexico border — believed they had found the young man.

How To Learn If Unidentified Remains Belong To Your Relative

Call the Colibrí Center For Human Rights at (520) 724-8644 and leave a message with your name, the name of the missing person and your phone number — or submit an electronic report. The organization collects DNA samples from families of missing migrants, and will be focusing on California in 2017. Sampling will occur in Los Angeles in February.

Since 2001, Hess’s office has analyzed the remains of more than 2,600 border crossers. About 900 remain unidentified. Fragmented skeletons like these are among the most difficult to identify.

Inside the pant pockets, to his surprise, Hess finds a cell phone with a SIM card, which yields the name of a Guatemalan man, Wilman Arrivai Vicente Perez. It appears the Aguilas were wrong.

Hess sends a bone sample to Tucson’s Guatemalan consulate, which located the Arrivai family and is awaiting a reference DNA sample. The Aguilas return to the desert. I follow.

'I don't see an end to this'

Aguilas Vice President Jose Genis notes the GPS coordinates of yet another human skull we find less than 10 miles north of the border. It's small, maybe a child's. Genis doesn’t think this skull belongs to Garcia.

Related: A Brother’s Fatal Journey Inspires Altruism

“I hope that someday we can actually stop what we’re doing, but I don’t see an end to this,” he says.

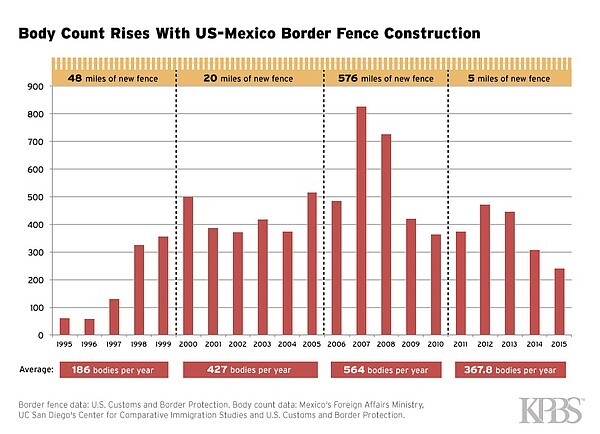

Border crossing deaths skyrocketed after long stretches of border fencing were built in the 1990s, rerouting migrant traffic into the desert, where hundreds perish of dehydration, heat exhaustion and other problems related to the extreme environment. Today, nearly 700 miles of fencing exist along the 2,000-mile border.

President-elect Donald Trump has promised to expand current fencing. The Aguilas believe this could funnel migrants into still-more dangerous crossing routes. Already, people are rushing to cross the border before Trump’s term begins. Some are dying on the way.

Over his walkie-talkie, Genis reads the coordinates of the most recent remains he has found to Aguilas president Ely Ortiz, who has stayed behind with some partners and our cars. The Aguilas can’t touch the remains — it may be a crime scene. Ortiz calls the location into local police, who will transfer them to the Pima County Medical Examiner for DNA analyses.

"There will be many, many more deaths," Ortiz says.

The Aguilas run into trouble

Genis decides it’s time to head out, even though we still haven't found Garcia. We have to be out of the desert before sunset, when potentially hostile smugglers inhabit this terrain. As we hurry out in our group of about 20 Aguilas volunteers, an unfamiliar voice comes on Genis’s radio.

“Identify yourselves!” it demands.

We stop and stare at each other, confused.

“Who are you?” one of the Aguilas asks.

Angrily, the voice says: “I can see you in your yellow shirts. Are you Border Patrol?”

“No, we’re not Border Patrol. We’re a humanitarian group for migrants who are in trouble. Who are you?”

The voice goes quiet.

“What’s happening?” I ask Genis.

Genis tells me that somebody has found our radio channel — probably a smuggler — and that we should quicken our pace.

“We’re almost at the cars,” he says.

As we make our way through the brush, we come across a phone. Genis keeps it in case it contains clues about a missing person.

Eventually, we are reunited with Ortiz and his partners. As we drive out of the desert, Ortiz expresses relief that the group didn’t end up running into the individual who spoke on our radio channel.

“What will happen the day we confront these people, what if they do something to us?” Ortiz asks. “For me, every volunteer is worth so much. They sacrifice so much. Time with their family. Their weekends.”

The risks for the group are continually rising as migrants are funneled onto narrower and narrower border crossing routes — the same ones used by drug traffickers. Meanwhile, the volunteers face environmental dangers, such as snakes and scorching heat. They must endure as much as 10 hours of walking in the desert, while carrying heavy backpacks full of water and safety gear. But the Aguilas remain committed to their mission.

“It’s not like we want to do it,” says Cesar Ortigoza, a 42-year-old Mexican-American plumber who has been with the group for three years. “We have to do it.”

In a nearby town, an Indian woman performs a traditional ritual, cleansing us with sage smoke. She says the spirit of the dead is clinging to our flesh — and that she must remove it.

'We’re dying of thirst!'

Back home, Genis charges the phone we found in the desert, and discovers that the seven most recent calls — on June 21, 2016 — were made to 911. Genis navigates to the phone’s contact list and calls the person’s family.

The phone belonged to a man named Martin Sarabia, who has been missing since he tried to cross the border in late June.

I request recordings of Sarabia’s 911 calls from the Pima County Sheriff’s Department.

In them, Sarabia can be heard begging for help in Spanish.

“We’re dying of thirst, we want water!” he cries.

Eventually, the call is transferred to a Joint Intelligence Operations Center used by BORSTAR, a Border Patrol search and rescue team that responds to 911 calls at the U.S.-Mexico border. The center doesn't record phone calls.

Sarabia calls 911 again and again. A dispatcher asks the man if he speaks English; she can’t understand him. Sarabia repeatedly gasps, “Can you help me?” and “Help!” His voice quivers with mounting fright. Again and again, the call gets transferred to the Joint Intelligence Operations Center used by BORSTAR.

In response to requests for comment about what happened after the county dispatcher stopped recording the calls, BORSTAR sent me the following emailed statement:

Multiple agents and an air asset conducted an extensive search in the area of the cell tower that transmitted his phone’s signal but did not locate the caller. Agents made multiple calls to the individual’s cell phone for several days but were unsuccessful in connecting with the caller.

It is uncanny that a banal-looking phone on the desert floor contains such a story. I think of all the other mysterious items we passed during our search. Signs of life were everywhere: tossed backpacks, sweaters, shredded female underwear, children’s toys, black gallon jugs. What sufferings are locked inside them?

'They don’t answer me'

I call Sarabia’s sister. She’s sobbing.

“I call the consulate and they don’t answer me,” says Rosa Elena Sarabia.

Relatives of missing border crossers are supposed to get in touch with their respective consulates in the United States. Many feel frustrated by the slow pace of the process and the seeming indifference of officials.

So many disparate bureaucracies are involved in the problem of missing migrants — Border Patrol, police departments, coroners, consulates, foreign affairs ministries of various countries — that families’ desperate questions often remain unanswered for what seems to them an eternity. The Mexican consulate in Tucson alone juggles hundreds of new cases each year. DNA analyses can take months, even years, as laboratories in the U.S. try to coordinate with foreign governments and families.

The Aguilas aim to speed up the process. Often, what takes the longest is finding the bodies, if that happens at all.

Martin Sarabia was a shy 22-year-old who wanted to work in construction in Phoenix. On June 13, eight days before he called 911, he called home and said he had run out of water, but that he only had one more day of walking to go and expected he would make it. That was the last time Sarabia's family heard from him.

They have been trying, in vain, to get help ever since. Then the Aguilas contacted them about the phone they found in the desert. The Sarabias now have a clue about what happened to the young man — but they still don't have conclusive answers.

'A sense of cultural threat'

Ortiz says few other people are willing to take on the risk of searching on foot the way the Aguilas do for anonymous migrants — especially as isolationist attitudes take hold in the United States.

Everard Meade, director of the University of San Diego's Trans-Border Institute, says a sense of "cultural threat" is stoking the rise of white nationalism amid calls for a border wall and mass deportations.

“I don’t think everyone who feels that threat is a white supremacist or that we should condemn them," Meade says. "It’s just that is how people perceive change. People perceive change as a threat.”

Meade says the Aguilas represent a counter-argument to this fear.

“We know that this issue is incredibly divisive,” he says. “And this is a way of using your own body, your own sweat, your own resources to weigh in.”

He says the Aguilas help transform migrant death statistics into human stories.

“If you’re from a family that has people of all different immigration backgrounds, and some people who are bilingual and some people who are Spanish speakers, there’s no them — it’s us,” he says.

The family of Marco Antonio Garcia is still trying to solve the mystery of what happened to their loved one. Máximo Garcia, the young man's great-uncle, says the family may ask the Aguilas to conduct a third search.

Aguilas vice president Genis says he is always eager to help the families of missing migrants.

"If they need help, we should just help," he says. "If they're willing to risk their lives and go through all this, then it must be a tough life for them. My life is pretty good right now. So why not help out?"