When the ominous beep of an emergency alert roused Mark and Kathy Allen out of bed in Sebastopol on Oct. 9, 2017, the Tubbs Fire was heading toward Santa Rosa.

So the Allens did too. They knew the assisted living facility where Mark’s mother lived was in the path of fast-moving flames. They sped toward the facility, called Villa Capri, the air smoky, the care home dark at two in the morning.

The building had no power. Almost all of the 62 elderly residents were still in their rooms. The Allens found the few overnight staff still left in the building.

“We asked them if they had an evacuation plan, and they said ‘No,’” Kathy remembers.

The couple hunted for residents, using cellphones as flashlights. Without power for the elevator, they bumped people in wheelchairs down stairs, through thickening smoke.

Many had dementia. “They just kept asking, ‘What's happening? Are you a first responder?’” Kathy said. “I'd say no, and then they'd ask again in five minutes.”

The Allens began carrying people in wheelchairs and walkers down the stairs at Villa Capri, working long into the night. Police arrived in the early hours to help move the last residents out.

One hour later, Villa Capri burned to the ground.

Mark Allen’s mother died a few months later.

“She died because of the fire,” he said. “She wasn’t killed by the fire, but because of the fire and the trauma that happened afterwards; it took all the will to live from her.”

The Tubbs Fire ate up swaths of Sonoma County where grass and oak woodlands meet urban sprawl. In recent decades, this sort of wildland-urban interface has attracted new development around the state even as fire risk has grown.

Built on a grassy hillside near rugged open areas, Villa Capri was always vulnerable. It remains so, along with Varenna, and thousands of facilities like it.

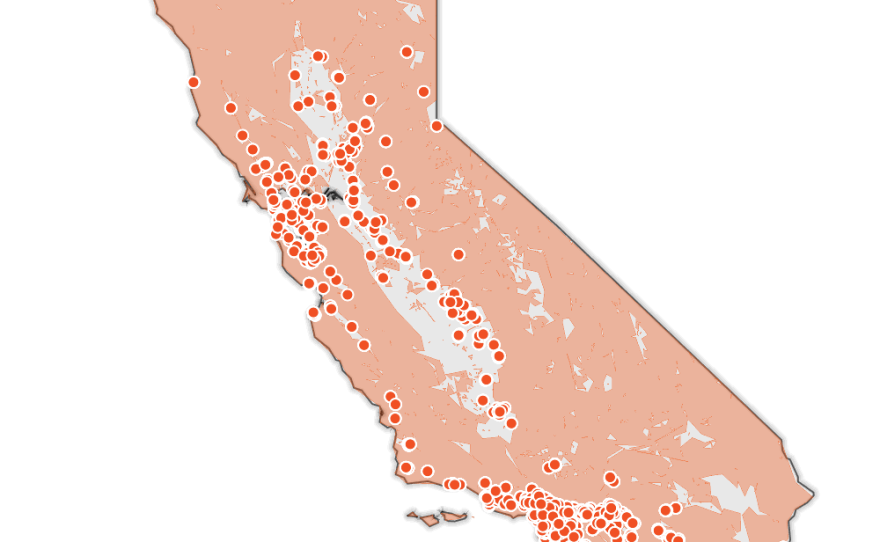

California regulates around 10,000 long-term care facilities, from small assisted living homes to large skilled-nursing centers. A KQED investigation has found that wildfire is a significant hazard at 35% of these facilities, in the wildland-urban interface, in state-designated fire hazard severity zones, or both.

A gray wave is crashing on California. The Golden State is aging faster than the rest of the country. In 10 years, the state projects the number of people 65 or older will be 8.6 million. And while demand for care facilities is curving up, critics say the laws governing emergency preparedness are weak and enforcement is lax. In addition, the pandemic is disrupting watchdog efforts and complicating urgent disaster planning even further.

As the coronavirus pandemic grinds on, this disaster planning is taking place against a backdrop of global heating, a dominant force shaping the fates of elderly people in long-term care.

“There is absolutely a colliding of the events of both population aging and climate change,” said Kathryn Hyer, a professor in the School of Aging Studies at the University of South Florida. “COVID-19 makes the already difficult situation of climate change and aging population worse.”

‘Like You’ve Really Been Abandoned’

Alice Eurotas, 87, is still haunted by the Tubbs Fire. She’s one of the people the Allens helped to escape three years ago. Rescuers took Eurotas to a Red Cross shelter, then a church. She has moved five times since that night. After a stroke, she’s now paralyzed on her left side.

“Leaving all of these elderly people, many of whom cannot walk, to fight the flames?” she said. “It felt terrible. Like you’ve really been abandoned.”

State and federal laws demand that long-term care facilities plan and train to keep residents safe in a disaster. At a Sequoia Living facility in Portola Valley, director of facilities and former fireman Ray Boudewyn has plans for fire, earthquakes, bombs and mountain lions, to name a few.

He also prepares for the days when wildfire smoke thickens the air indoors, he says. The body’s defenses against smoke pollution decline with age, and Sequoia plans to bring in HEPA air filters or run HVAC systems if it needs to combat the effects of a fire.

“The residents may have compromised immune systems,” Boudewyn said. “They may have respiratory issues, cardiac issues.”

Those same problems make evacuations difficult.

“I've got to get them in a safe zone,” Boudewyn said.

Because of smoke, safety could be a hundred miles away.

Yet evacuations themselves may be riskier than sheltering in place, especially when older people move multiple times. Nationwide, at least half of nursing home patients have dementia, a condition that gerontologist Lisa Brown has found raises the risk of death in the months just after a disaster.

This underscores the critical need for planning, says Brown, who directs the Risk and Resilience Research Lab at Palo Alto University.

Brown says residents like Alice Eurotas may experience psychological trauma from losing relationships and networks they depend on.

Eurotas now lives at a nursing home in Petaluma. She is depressed and angry, says her daughter.

Beth Eurotas-Steffy is angry, too.

“I can't even really put into words how angry I was and how disappointed in the state agency whose job it is to get up every morning and protect people like my mom living in a facility like that,” she said. “And they failed them.”

Consultants, Not Disciplinarians

Assisted living and nursing homes both have basic responsibilities for residents’ safety and well being. But they serve different purposes and follow different rules.

About 2,300 intermediate-level and skilled nursing homes in the state employ medical professionals to provide health care. These facilities are licensed by the California Department of Public Health. Because they accept Medicare patients, they’re subject to more demanding federal regulations.

A different state agency, the California Department of Social Services, oversees about 7,600 residential communities for the elderly; unlike nursing homes, they aren’t health care facilities. Instead, care workers simply assist with daily living activities like bathing and using the toilet.

Fire Risk for All California Long-term Care Facilities

Only Facilities in Risky Areas

Source: Cal Fire’s Fire Hazard Severity Zones, SILVIS lab at the University of Wisconsin Wildland Urban Interface, California Department of Social Services regulated facilities, California Department of Public Health regulated long-term-care facilities, and Natural Earth.

By law, both types of care homes must do emergency planning, training and fire drills.

Villa Capri had an emergency plan. But one worker didn’t know about it. Three workers had never participated in a fire drill. According to the state’s accusation and a complaint investigation, the workers couldn’t locate keys for buses that could have been used for evacuation.

In a proceeding against Oakmont Senior Living, the company responsible for Villa Capri and Varenna, the state accused administrators at both facilities of abandoning around 100 people that night almost three years ago.

“That was a real eye-opener for us, that staff weren’t trained,” said Pam Dickfoss, who oversees licensing of assisted living facilities at the California Department of Social Services.

At the time of the Tubbs Fire, state law required facilities to have evacuation procedures, transportation for residents and a plan for self-reliance for 72 hours in case of disaster.

But Dickfoss said facilities weren't thinking about wildfire.

"They typically had plans for a fire within their facility, a fire in the kitchen," she said. "But not plans to actually evacuate everyone out of the area. And so they weren't prepared to make sure they had transportation. It's a large facility. How are they going to get, you know, 200 residents out of a facility?"

Because of what happened during the Tubbs Fire, the Department of Social Services issued multiple citations to the care homes. Regulators moved to revoke their licenses and those of their administrators.

But after an appeal, the state settled and put the facilities on probation.

Oakmont has paid no fines; together, its two facilities have paid “monitoring fees” totaling $10,068. One month’s rent for one person at either of the homes can run up to that amount.

Oakmont Senior Living did not respond to requests for comment.

As a direct response to the abandonments, lawmakers passed AB 3098, establishing stronger emergency planning rules.

That new law requires facilities to train and drill staff more often; make keys available; install evacuation chairs at stairwells; and designate two potential evacuation destinations, including one out of the area.

But regulators have rarely penalized homes over inadequate planning.

In 2018, state inspectors cited just 62 facilities for having an insufficient disaster plan or training. Last year, when the law took effect, they cited 239. A KQED analysis found that’s 3% of facilities statewide.

The department acknowledges regulators prefer to offer guidance and technical support rather than issue citations.

Dickfoss says inspectors see themselves more as consultants than disciplinarians.

“It's really a collaborative effort across the state between the providers, between the advocates and the department,” she said.

Few beds are available for low-income seniors, Dickfoss says, leaving those residents “one step away from being homeless” if a facility closes. A 2017 California Health Care Foundation report projects that the demand for beds at assisted living facilities will double over the next 20 years, while supply will run out in about 10.

Dickfoss defended the ultimate decision not to close Villa Capri and Varenna by citing the delicate balancing act her department conducts between protecting residents from rising fire risk and ensuring enough beds to accommodate the growth of the state’s aging population.

Critics like advocate Chris Murphy argue the department’s approach to enforcement is wrong, absurd and dangerous.

The Department of Social Services “will rarely come down on the side of the consumer,” said Murphy, who directs the watchdog group Consumer Advocates for RCFE Reform. The department is functioning as “a provider protection agency, not a consumer protection agency,” she said.

Little Followup for Rule Violations

A generator chugs outside a beat-up brown-and-beige RV parked on a wide boulevard deep in the San Fernando Valley. Randy Odette lives here with a cat and a dog. The pavement shimmers with heat. Behind her, the hillside grass is brown, too.

“The mountain is pretty dry up there,” said Odette. “But that's California.”

Over the last 12 years, three wildfires have threatened this Sylmar neighborhood. Odette’s mother lives nearby at the Astoria Nursing and Rehabilitation Center.

Public records show the California Department of Public Health caught 78% of nursing homes violating fire safety and emergency planning standards over a two-year period.

Among them is Astoria, where Odette’s mother contracted COVID-19. Betty Odette is a tiny, 96-year-old woman in the late stages of Alzheimer’s. She is now recovering from her bout with the coronavirus.

COVID-19 outbreaks have struck California nursing homes with fatal frequency. Los Angeles County counts 25 coronavirus deaths at Astoria. Since March, the facility has reported more than 140 cases, sickening residents and health care workers.

Emergency preparedness regulations are meant to safeguard residents of nursing homes against pandemics as well as disasters like wildfire.

Federal auditors spot-checked 20 nursing homes in late 2018 to monitor the state’s enforcement of emergency preparedness standards. (One of these homes burned to the ground in the Camp Fire after the visit: Cypress Meadows, in Paradise.)

Eighteen of the homes failed to meet some standards. When state surveyors followed up afterward, more than half of the facilities had similar problems.

The federal audit recommended the state make more in-person inspections and offer training on life-safety codes to facilities. CDPH rejected those findings, saying it lacked staff and resources.

Examining the same rules federal auditors did, KQED found that in a two-year period, state health surveyors considered few emergency preparedness or fire safety deficiencies severe enough to require a follow-up visit: just 6%.

Those federal nursing home regulations were a long time coming. Four hurricanes crossed Florida’s panhandle in 2004, threatening hundreds of care homes. Then, after Hurricane Katrina, flooding swallowed St. Rita’s nursing home south of New Orleans. Thirty-five people died.

After that tragedy, federal watchdogs recommended better emergency preparedness. For a dozen years, industry lobbying groups fought to weaken and delay proposals even as natural disasters became more common. “New” emergency requirements only took effect late in 2017.

Facility managers say it’s rare to get through an inspection without a violation. They also say some failures are worse than others.

“I think that’s pretty serious, if you don't have an emergency plan,” said Sequoia Living’s Boudewyn, who oversees nursing homes in Marin, Mendocino and San Mateo counties. “I don't really understand how you could even get licensed.”

At the Astoria nursing home in Los Angeles County, Odette asked the administrator to see the facility’s emergency plan. He would tell her only that regulators had approved it. Then he pointed her to a map on the wall, showing where the emergency exits are.

Now Odette says she’s scared. And angry.

“The state has got to be responsible for these homes,” she said. “I mean, they can't help themselves, the patients. And it's really not up to the staff.”

Inadequate emergency preparedness should be considered an immediate harm, argues Pat McGinnis, executive director of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform. That would result in more fines. She thinks regulators should prevent unsafe facilities from accepting new patients — and pocketing monthly fees.

“You need to be able to hit them where it hurts,” she said. “That's not going to be in their hearts. That's going to be in their wallets.”

Dr. Mike Wasserman of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine says nursing home operators limit their financial liability with webs of corporations — different companies for property, for operations, for management. That makes fines just a small cost of doing business.

Wasserman calls nursing home real estate owners “slumlords” who absorb the cost of fines easily.

“You can just ask yourself where that's going to end up from a quality perspective,” said Wasserman. “Where that will end up in a fire. Where that will end up in a pandemic.”

“We're seeing the results.”

Pandemic Compounds the Risk

When a fire threatened San Luis Obispo in late June, half a dozen assisted living homes moved most residents to hotels under an evacuation order. Some family members came and took their loved ones home.

But when fire officials gave the all-clear, area ombudswoman Karen Jones says neither the state nor the county required facilities to separate residents who stayed with family from those who remained quarantined in hotels.

And that’s only one example of how evacuations are more difficult in the pandemic.

So far, federal and state authorities offer only general advice about disaster response in a pandemic, like recommending more shelters that can accommodate social distancing.

“We have to have it in our minds that grouping people together and shoving them off in a hurry to one location might present an equal if not greater life-threatening risk,” said Vance Taylor, part of the executive team at the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services.

At Cascades of Grass Valley, an assisted living center, director Pepsi Pittman has wildfire evacuation agreements with sister facilities out of the area, but when she tried to set up similar agreements with hotels in Sacramento, where residents could isolate in individual rooms, she struck out.

Hotel staff told her the rooms are filled with nurses “who aren't going home because they're treating COVID-19 patients.”

Pittman isn’t the only facility director in Grass Valley in need of robust evacuation plans. In Nevada County, much of which sits in Tahoe National Forest, every long-term care home faces a heightened risk of wildfire.

Fire Risk for Skilled Nursing Homes

Skilled Nursing Homes With COVID-19 Outbreaks

Source: Cal Fire’s Fire Hazard Severity Zones, SILVIS lab at the University of Wisconsin Wildland Urban Interface, Natural Earth. California Department of Public Health regulated long-term-care facilities, and and nursing home outbreak data accessed on August 2, 2020.

At Sequoia Living, Ray Boudewyn is managing the overlapping risks of coronavirus and wildfire prep using the same emergency command structure police and firefighters do – one commander, with clear responsibilities for everyone below. None of his three facilities have reported any cases of COVID-19 among residents.

“You can see the body language from the staff,” he said. “They're worn out. I mean, this has been an active situation since late February … it's kind of like a war. “It doesn't go away.”

What’s the Backup Plan? Call 911

One way to protect older and disabled people in care homes is to demand more scrutiny for their emergency plans. Kathryn Hyer, the University of South Florida gerontologist, says climate-driven storms have forced Florida to do just that.

“There's a real effort to make sure that that communication occurs so that people can talk to each other during a local emergency,” Hyer said, “ask for help, ask for supplies, tell them that they need to evacuate or whatever needs to happen.”

Hyer says Florida law requires long-term care homes get approval for disaster plans from emergency officials and requires regulators to check up on them.

“And if they don't find it, they fine either the assisted living or the nursing home for not having that plan,” she said.

But California doesn’t do that. No law requires CalOES or county emergency managers to look at the plans that care homes make for wildfires or any other threats.

In Sonoma County, KQED’s analysis found three-quarters of long-term care facilities are in fire-prone areas. Long-Term Care Ombudswoman Crista Barnett Nelson said she is “100% confident” that not all of the residences know how they will execute a plan in case of disaster.

The county regularly holds “table top” exercises to practice for disasters, says Director of Emergency Management Chris Godley, but they’re optional for long-term care homes.

Godley says he is “encouraging these facilities” to “develop realistic emergency plans, not just hypotheticals that sit in a binder on the nurse's station.”

Sonoma has increased outreach and added more early-warning systems, but Godley worries that the backup plan for underprepared facilities is still just a 911 call.

“Technology is great, but it does not wheel a bed out of a home into an appropriate ambulance,” he said.

What’s needed long term, he believes, is a change of mindset: planning for disasters as a way of life, not a last-minute scramble.

In California, public officials talk about “vulnerable populations” for whom the coronavirus is a greater threat.

Climatologist Katharine Mach questions the use of the word “vulnerable” to describe older people and residents of long-term care homes. She says it’s often used to suggest weakness.

Systems like health care, transportation and planning are essential, and like the people they serve, they’re vulnerable too.

Mach points out that people who have lived a long time have developed resilience.

“Those are individuals who have … overcome so many challenges and have persisted and helped shape the fabric of our society,” she said. “There's a whole lot of resilience there that needs to be tapped as we all find solutions together.”

Older and Overlooked is a special investigative series by science and news reporters at KQED. KQED is the NPR and PBS member station for Northern California, serving audiences across the state on air and online with compelling stories that inform, inspire and involve.

CalMatters contributed data analysis, editing and graphic design to this project. CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

Capital Public Radio contributed photos to this series. As the NPR member station based in Sacramento, CapRadio serves California’s Capital region, Central Valley and Sierra Nevada.