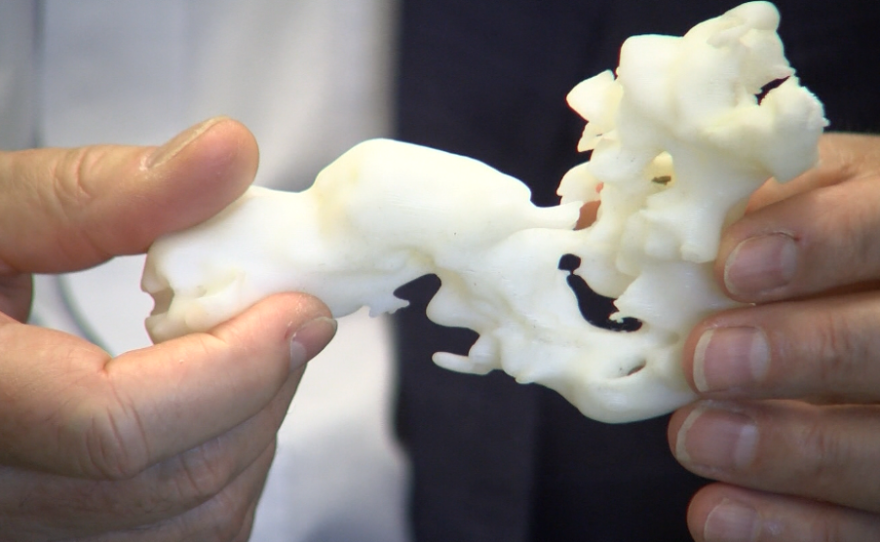

UC San Diego's Larry Smarr is the kind of guy who wears a Fitbit, monitors his sleep and has had his DNA sequenced. But he takes the whole self-tracking thing farther than most. He has mapped his internal organs in three dimensions. He even has a 3-D printed model of part of his colon — the part cut out in a recent surgery.

"Just this amount of my body was out of control," Smarr said, clutching the plastic replica. "And to be able to actually hold it was very empowering."

Smarr has an inflammatory bowel disease. When he learned that part of his colon needed to be surgically removed, Smarr got to wondering: If 3D graphics are increasingly being used to bring video games and other forms of entertainment to life, why could they not be used to help protect his life?

In an unusual approach to this kind of operation, Smarr and his surgeon decided to use 3-D imaging in the planning and execution of his recent colon resection surgery. They said the experiment was a success. And now, the man known for evangelizing the concept of the "quantified self" is on a mission to popularize the idea of "quantified surgery."

the prospect of going under the knife has one scientist wondering. Three the graphics are used to bring video games to life why can't they be used to protect his life. David Wagner has this story on the unusual approach that this professor took for his own operation. Larry Smarr is a kind of guy who wears a fit bit monitors his sleep and has had his DNA sequence. He takes a whole self tracking thing farther than most. He is showing me a 3-D printer model of part of his: the part cut out in a recent surgery. Just this amount of my body was out of control. To be able to hold the was very empowering. Smarr has inflammatory bowel disease. He is happy to show them to you in virtual reality. For four years I've been giving the insides of my body. In a dark room the US San Diego Institute Smarr leads he is pulling up a 3-D map of his colon. He recently brought his surgeon to show her the bunched upset and causing trouble. He wanted her to see what you would have to cut out before the operation. Leading up to his surgery Smarr was bothered by the thought that this kind of imaging is not already used in the operating room. His surgeon of US -- UC San Diego health felt the same way. I have teenage boys and I look at the video games and it kills me every time how is it that we have great gaming graphics of technology and none of that has been applied to surgery and simulation. Smarr proposed an idea. Why not incorporate the 3-D map into his surgery. She says this is not the typical approach but she was for it. He was able to help me visualize more and put me through a simulation of what it would be like to operate on him before I operated on him. She says searches are already good at preparing successful: resections. They do encounter unique challenges with each paycheck challenges they would be better off knowing about for the patient goes under. 3-D imaging is already using some other types of surgery but she thinks bowel operations could be improved by a GPS for surgery she says it could be like drivers using Google maps to find the best route through an unfamiliar area. That the same information I need. Stakes are high in the operating room. She had the 3-D map of Smarr : through the surgery. She drafted UC San Diego computer scientists into the operating room. He's the one that created the 3-D map. He has no formal training to assist in surgeries but who's there to help surgeons during the operation. Going into that surgery I was definitely a nervous wreck. Not only was it an actual surgery on a human that also a surgery on a human that I've worked with. It all worked out fine. Now she wants to use 3-D imaging with more of her patients in the hopes of standardizing this approach. I think that's going to be something we start here at UCSD and shift what we do worldwide in surgery. A few months after the surgery Larry Smarr continues to recover well. Some patients may have been freaking out. Smarr says turning himself into a guinea pig reduced his anxiety. As a patient your fundamental enemy is the unknown. That's what drives anxiety. That's what drives fear. As a patient, I was learning and helping to form the game plan for what was going to be done to my body. That reduced all kinds of uncertainty. Smarr likes to say his job is to live in the future and report back. If this is the future of surgery he said if the future were patients will feel more in control of their health care even when they are under anesthesia. David Wagner KPBS News. Joining me is Smarr -- Larry Smarr welcome Larry. We just heard the 3-D map of your: was created by layering MRI images one on top of the other. What do you see in the 3-D image that you cannot see in the MRI? The radiologist are highly trained to be able to look at 2-D MRIs and visualize in their head with the 3-D looks like. They are extraordinary people but the surgeons work differently. They work in 3-D. As Mike surgeon said she doesn't think 2-D is very useful because she wants to see it in 3-D like on a videogame. We heard the 3-D images have been used in other kinds of surgery before. Would it be fair to say that this is becoming a frequent tool that surgeons use? It depends on where the surgery is going to take place. If it's brain surgery, absolutely it's been used for a number of years and it is critical. If you are doing vascular surgery on an individual artery or vein that is a localized object. It does not move much. It's quite useful they are. Sometimes it's used within a kidney. To do the whole abdomen have your liver, small intestine, large intestine, bladder, spleen all of these things and every time you are breathing it moves. It's a much more challenging area. This was the first time at UC San Diego health that they were able to use a 3-D realization of the anatomy. How expensive is it to have this 3-D map done? Would be accessible to the average patient? It uses the kind of GPU processing unit that's in your gaming computers that the kids are using. The software is a critical aspect of it. In computer graphics as a field where I worked for 20 years, we have known how to do this for a long time. It has not been requested that much often because the radiologist are the people who are most involved with looking at MRI and like I said they can do it in their head. The innovation here was that the surgeon wanted to have the 3-D and she wanted it so much that after we used it she could plan my surgery. She wanted it in the operating room. She drafted my virtual reality expert into the operating room. He was running a PC. This is another example where the consumer market is so vast now with smart phones and PCs that it drives down the cost of the technology in a way that if those only the medical community that it would be very expensive. If they can learn to adapt the consumer technology than it should be inexpensive. Do you see this kind of highly personalized medicine changing the way medicine is practiced? Absolutely. We have seen this movie before. If you go back to when I grew up in the 50s, our automobiles we knew something was wrong with them because smoke them out of the engine. Why that point you had a chronic disease. They had to put a chain around your engine and political and it was a huge operation. Today because of the micro processor revolution they just keep track of time series and other vital signs in your automobile. You go in for preventive maintenance every 20,000 miles and compares everything across the country over the network and then they know something is beginning to go wrong. They corrected before it becomes a problem in your car keeps running beautifully for another 200,000 miles. That is where we are going with medicine. Your car is completely personalized to your car. You would not imagine it being any other way. You've been given virtual tours of the inside of your body to hundreds of people. Has seen you the internal makeup of your body change the way you think of yourself? Absolutely. Almost everybody it never occurred to me to wonder what was inside of me and how was it different than what's inside of you. It varies in detail from person to person. How crazy is that. The thing you live with your entire life is your body. How can you not know what's going on? What else in your house would you not want to know how to work or at least what signs to look for. When I was a kid in the 60s with the invisible man -- I suspect young people will grow up exploring their own bodies. First year medical student should get an MRI and use their personal bodies. Compare their bodies with each other. Like through Facebook we will be sharing in virtual reality is the new communications media. Imagine medical students doing that and learning about the diversity of human bodies on themselves before they have to start upgrading -- operating on strangers. I've been speaking with Larry Smarr. Thank you so much. My pleasure.

Smarr is very open about his experiments with self-tracking. He is happy to offer people an X-ray view of his body in virtual reality.

"Actually for four years, I've been giving tours of the inside of my body to hundreds of people," he said.

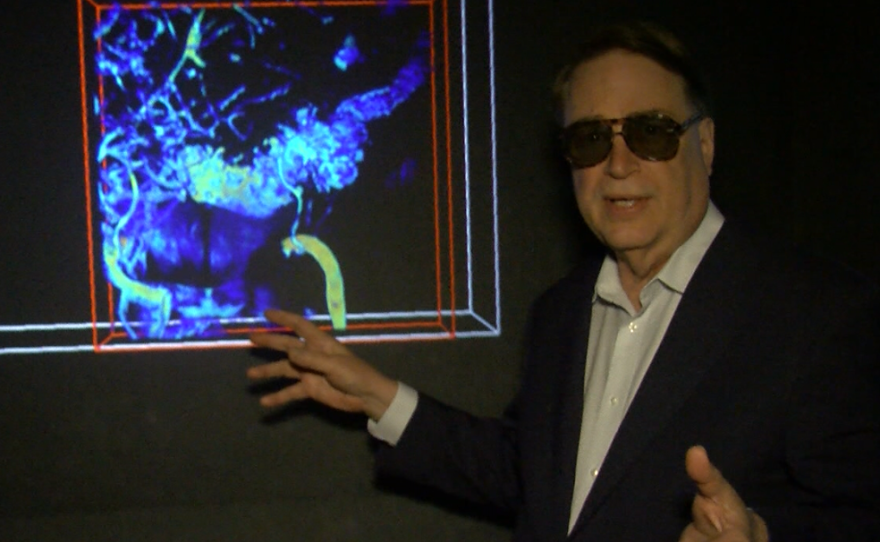

In a dark room at Calit2 — the UC San Diego institute Smarr leads — a computer scientist is pulling up the 3D map of Smarr's colon. The black walls in this "virtual reality cave" surround visitors. Projected onto them is a huge, floating image of Smarr’s insides.

"This is my entire colon," Smarr said, wearing a pair of 3-D glasses. He recently brought his surgeon into this space to show her the bunched up section of his colon causing trouble. He wanted her to see exactly what she would have to cut out before the operation.

Leading up to his surgery, Smarr was bothered by the thought that this kind of imaging — which has been possible for years — is not already used in the operating room. When he brought this up with his surgeon, Dr. Sonia Ramamoorthy of UC San Diego Health, he found that she felt the same way.

"I have teenage boys," she said. "I look at their video games, and it just kills me every time to think: How is it that we have such great gaming graphics and technology and none of that has been applied to surgery and simulation yet?"

Smarr proposed an idea. Why not use this 3-D map to help guide his surgery? Ramamoorthy said this is not the typical approach, but she was all for it.

"He was able to sort of help me visualize more, and put me through a kind of simulation of what it would be like to operate on him before I operated on him," she explained.

Ramamoorthy said surgeons are already good at performing successful colon resections. But they do encounter unique challenges with each patient — challenges they would be better off knowing about before the patient goes under. Perhaps better imaging could reduce the time patients spend in surgery and help them recover faster, she said.

Ramamoorthy notes that 3-D imaging is already used in some other types of surgery, including vascular and liver surgery. But she thinks bowel operations could also be improved by having a kind of GPS for the surgery. She said it could be like drivers using Google Maps to find the best route through an unfamiliar area.

"You want to route it out so you make the most efficient turns, and so that you're aware of any accidents in the area so you can bypass that stuff," Ramamoorthy said. "That's the same kind of information I need before I go into the operating room to operate on someone. I mean, the stakes are high in the operating room."

Ramamoorthy had the 3-D map of Smarr's colon on display throughout his surgery. She even drafted Jurgen Schulze, a UC San Diego computer scientist, into the operating room. He is the one who created the 3-D map by painstakingly layering two-dimensional MRI images, one on top of another.

Schulze has no formal training to assist in surgeries, but he was able to help surgeons refer to this 3-D map during the operation.

"Going into that surgery, I was definitely a nervous wreck," said Schulze. "Not only was it an actual surgery on a human, but it was also a surgery on a human that I've worked with for a good 10 years."

Despite Schulze's anxiety, everything turned out fine. A few months after his surgery, Smarr continues to recover well. He relied on his Fitbit to make sure he walked a little more each day during the early stages of recovery.

It remains to be seen whether other bowel surgeons will want to incorporate 3-D imaging into their operating rooms. Ramamoorthy said she is enthusiastic about the idea. She plans to use 3-D imaging with more of her patients in the hopes of standardizing this approach.

"I think that's going to be something that we start here at UCSD that's just going to profoundly shift what we do worldwide in surgery," she said.

Some patients might have been freaked out by the idea of tinkering with a tried-and-true approach to surgery. But Smarr said turning himself into a guinea pig actually reduced his anxiety.

"As a patient, your fundamental enemy is the unknown," he said. "That's what drives anxiety. That's what drives fear. And as a patient, I was learning and helping to form the game plan for what was going to be done to my body. That reduced all kinds of uncertainty."

Smarr likes to say his job is to live in the future and report back. If this is the future of surgery, he said, it is a future where patients will feel more in control of their health care — even when they are under anesthesia.