She had spent weeks writing and practicing, capping off preparations that morning with a tasteful pair of heels and a mature lip color. Now middle school student Gloria Hohenstein had 20 sets of eyes on her.

"Ready?" her teacher Ellen Berg asked.

"Yes," Gloria answered, her breathing heavy with nerves.

From a row of judges, Berg said, "I would love to welcome everybody to Gloria's eighth-grade exit portfolio."

The next ten minutes would determine whether Gloria passed eighth grade and moved on to high school. She had to convince the panel she has grown in all aspects of her life, including public speaking.

"Hi, my name is Gloria," she started. "I would first like to start off with community service."

She moved through the next lines cautiously, like steps on a tightrope.

The presentation is part of San Diego Cooperative Charter School's focus on social emotional learning, or — put very simply — developing relationship, communication and stress management skills. It is a kind of instruction gaining traction in schools across the county, and it is picking up speed as the state rolls out new school accountability measures and teaching standards for social emotional learning.

"This is really the essential work," said Kate Dickinson, who spearheads the effort at SDCCS. "This is the essential work into growing humans who are able to engage in the world in a really meaningful way."

Educators often describe it as "supporting the whole child," meaning it is not enough to teach academic subjects if students lack the social and emotional skills needed to take in the information and put it to work.

That was the case for Gloria in elementary school.

"We used to call her the Velcro kid," said Soledad Mason, one of Gloria's moms. "No matter where we were, even if there was a really interesting distraction, like, at the park or something like that, she'd stay very close to us."

She was a shy kid. And that was OK, Mason said, until Gloria fell behind in reading.

"Being so reticent, she wasn't asking for help," Mason said. "Teachers weren't really paying attention to her because she was well behaved, but she needed help."

So Gloria's parents enrolled her in SDCCS in Linda Vista, hoping she would come out of her shell just enough to thrive.

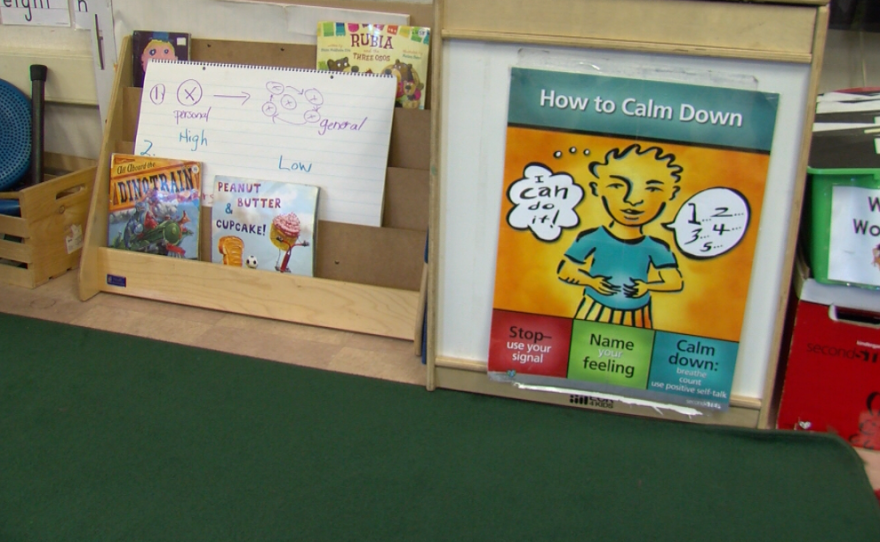

The K-8 school teaches social emotional skills in standalone lessons. "How to calm down, how to solve a problem, how to name a problem, how to work with a peer, how to join a game, how to initiate a conversation," Dickinson rattled off.

But it also infuses the work into nearly everything it does. Elementary recess staff are trained to look for teachable moments on the playground. At the middle school level, students are expected to advocate for themselves, not send their parents calling.

Gloria's other mom, Ellen Hohenstein, recalled being almost brushed off when calling about a class schedule change. She was told Gloria would have to work it out on her own. "I was really shocked at first, and now I wouldn't even think I would need to speak for her," Hohenstein said.

Advocates of social emotional learning say building this kind of agency and emotional intelligence among students is necessary groundwork for academic learning.

"It doesn't replace core academic skill instruction. It allows students better access to that skill instruction," Dickinson said. "When there are fewer conduct problems and behavior problems, when children are able to connect with one another and solve their own challenges, students are then spending more time in class focusing on academic learning."

That may be true for SDCCS students, but it does not bear out on standardized tests. Using state data, the California Association of Charter Schools ranks both SDCCS campuses (it has another in Mountain View) in the bottom 10 percent when compared to schools with similar demographics, though the 14-year-old school did recently see gains on its test scores.

Dickinson said academic achievement at the school tends to be flat in earlier grades, then makes a steep climb in middle school.

"Sometimes our kids come to us and they have a lot of social emotional needs," she said. "And what that may mean for our youngest students is that we spend a significant amount of time on those social and emotional skills early, so that once they are in a great spot to access academic skills, their rate of growth is really significant."

The pattern bears out in national research, too. A recent review of 37 studies showed students in schools with social emotional programs, on average, rose 11 percentile points on either their report cards or standardized tests. On report cards, that is roughly a letter grade increase.

But SDCCS likes to point to other indicators. It has zero suspensions and expulsions. And it scores high on a statewide school climate survey that looks at bullying, feelings of safety and belonging, and motivation to learn.

The same indicators are now factored into how the state measures school performance. This year it released the California School Dashboard to give parents a more holistic look at how schools are doing.

SDCCS recently partnered with the University of San Diego to study the long-term outcomes of its students. They are in the beginning phases, but may look at whether students go on to volunteer or work in the public sector. USD has housed the Character Education Research Center for more than two decades and is recognized by the state as a leader in the field of social emotional learning.

Researchers and educators like Dickinson are, in some ways, scrambling to build up more evidence to seal social emotional learning's credibility in the eyes of parents and administrators.

"With any model in education, especially one where we know the long-term outcomes outweigh the short term benefits, we have to make a commitment to stick it out and play the long game with kids," Dickinson said. "We can't abandon this work too early."

For now, it seems the work will only ramp up in San Diego County. Mara Madrigal-Weiss, the County Office of Education's student mental health and wellbeing coordinator, said her trainings on social emotional learning are always well attended by the region's 42 school districts.

She plans to add more next year, saying the skills are crucial for students heading into a workforce that values so-called soft skills such as collaboration and flexibility. But Madrigal-Weiss said parents should not see this work in schools as "soft."

"I think self discovery, self understanding is not an easy journey," she said. "It takes a lot of work to be thoughtful, to go inside, to understand the various feelings and emotions and your place in society. And those are skills you're going to need the rest of your life. That's not soft."

San Diego Unified has been using a social emotional curriculum called Second Step for about 10 years. It, too, plans to offer more training for staff next year.

Teacher-credentialing programs are increasingly including social emotional learning in their curriculum for future teachers, though it is not required. National University recently launched a program called Sanford Harmony that brings social emotional tools to teachers in the region. It also has a research arm that will track outcomes and inform what it teaches in its credential program.

Shulamit Ritblatt, a child and family development professor in San Diego State's College of Education, said she is relieved to see this kind of momentum around social emotional learning.

"Many times, social emotional development is only talked about when there is bullying or a crisis," she said. "Schools need to build social emotional development into their foundation as prevention, and weave into all subject areas and interactions."

That is what's happening at SDCCS. The result for at least one student there: public speaking with ease.

"And lastly I'd like to talk about personal growth," Gloria said, commanding her makeshift stage and making eye contact with the panel.

"When I first entered this school, I was very closed up and I was shy and I was quiet," she said. "And because I came from a school where you were taught to be this one thing and we're going to mold and we're going to shape and we're going to break you until this is who you are, I closed down even more. Because at this school, you were planted in a pot and told to grow, and I wasn't used to that. So I'd like to thank this school for helping me come to be who I am."

Gloria earned an "outstanding" on her portfolio presentation. "You've got maturity, you've got sincerity, and I love that you're looking for the meaning in things. Keep doing that," her teacher Ellen Berg said.

Next year, Gloria will attend Patrick Henry or Helix High School. Her poise makes it hard to believe she is not already there.