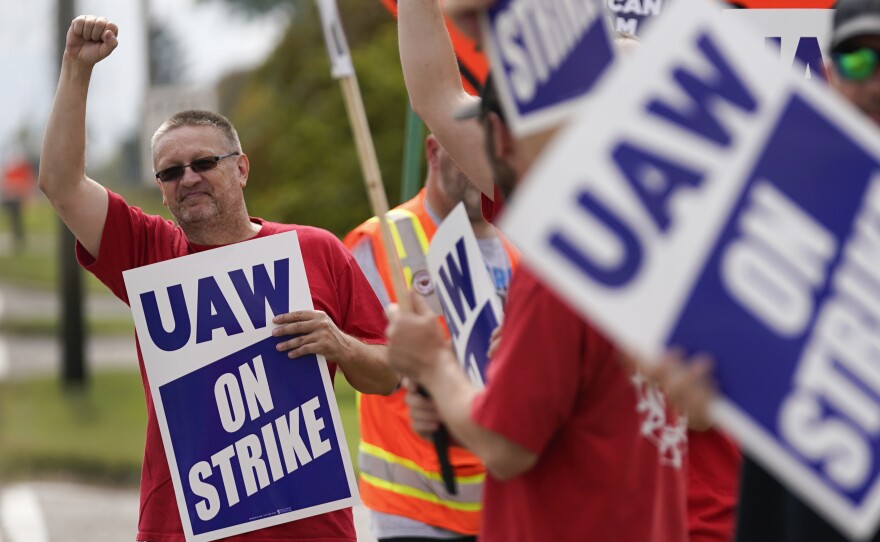

As the United Auto Workers strike is set to enter its third week, one thing is for certain: The union is prepared for a long fight against the Big Three automakers.

For the first time in history, the UAW is striking against all of the Big Three — GM, Ford and Stellantis — at once.

But it's gradually escalating the strike, instead of having all of its 146,000 auto workers walk off their jobs at once. That approach is intended to keep the companies guessing, making it difficult to pinpoint exactly how long the automakers can withstand a strike without a major hit to their business.

It's also intended to stretch the UAW's strike fund, which totalled $825 million before the first set of union workers walked off their jobs on Sept. 14.

The UAW's strategic and targeted approach could make this a prolonged fight — but there are still realistic limits to how long any strike can last.

Here's a look at the UAW's strategy, and the financial impact it could have for the unions and the automakers.

For automakers, a lot of blows but no big punch

So far, the UAW has refrained from targeting the most profitable sectors of the companies' production – a strategy that, if maintained, positions the companies to withstand an ongoing strike for many months.

"They're not hitting at the heart of the companies," said Sam Fiorani, vice president of global vehicle forecasting at Auto Forecast Solutions. "They're allowing the companies to still stay in business – and just giving them enough pain to stay at the table."

The union has yet to target plants where the automakers manufacture their most profitable vehicles: full-size trucks. If they do, it could have a "nuclear effect," Fiorani said, impacting the companies' production and sales to a far greater degree.

Pick-up trucks and large SUVs are the "bread and butter" of the Detroit 3, said Michelle Krebs, executive analyst at Cox Automotive, adding that this is the time of year – leading up to the winter months – when sales go up for these highly-profitable vehicles.

A strike expansion to the plants that make them would change the companies' outlook as the strike continues.

"Week to week, we're trying to guess what they're going to do next," Krebs said.

But the automakers may be starting to feel the pain

The UAW may have opted to hold off on a knockout punch so far, but it's still delivering enough pain to the Big Three.

The strike has already had a "substantial" impact on Ford, according to Kumar Galhotra, who leads Ford's internal combustion business. Galhotra, in a call with reporters, declined to share exactly how much the company is losing each week.

David Whiston, an auto stock analyst at Morningstar, estimates that if workers were to go on strike at all facilities, GM could hold out for six months and Ford for ten months, before reaching the minimum level of cash needed to run their business.

But since only a fraction of the companies' facilities are currently on strike, the automakers can likely last much longer than that.

Roughly 25,000 auto workers have walked off the job so far — still less than one fifth of the auto workers represented by the UAW.

In addition, more than 3,000 workers across the Big Three automakers have been laid off temporarily as a result of the strike. On Wednesday, Ford announced it will lay off an additional 400 workers from two plants.

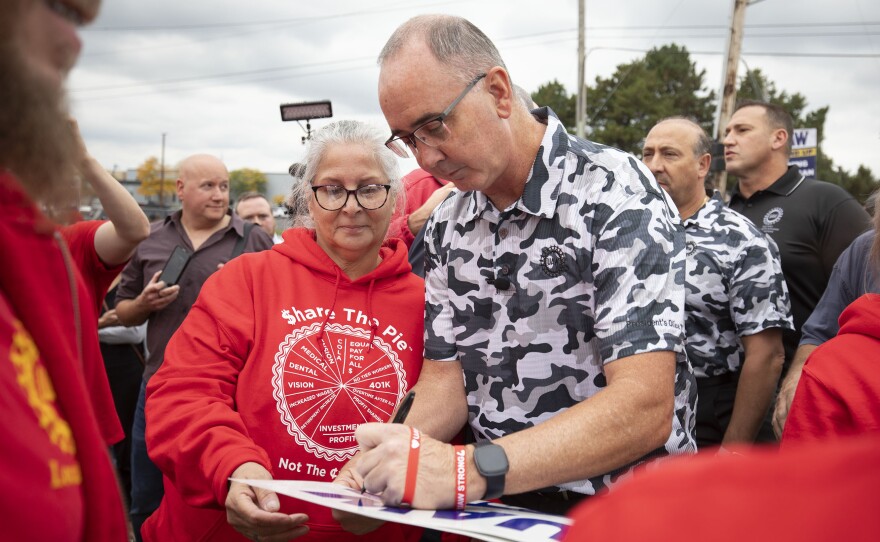

"We are seeing UAW really sort of taking an approach where they are strategic about how to exert pressure on the company, without damaging suppliers ... and without damaging the national economy," said Karla Walter, senior director of employment policy at the Center for American Progress.

That said, the UAW has made clear it will continue to tighten the screws as it looks to pressure the automakers to reach agreements sooner rather than later – while the strike is still relatively measured in its approach and scale.

The UAW aims to stretch out its fund

The gradual strike expansions offer another advantage to the UAW: The strategy will help protect the longevity of the UAW's strike fund, which amounted to more than $800 million when the strike began.

Workers on strike would see a hit to their incomes. The UAW says workers who are on strike are receiving $500 per week in payments from the strike fund, starting on their eighth day off the job.

Workers laid off from other facilities as a result of the strike will also receive $500 per week from the strike fund, the union says, as most of them will not be eligible for unemployment benefits.

On average, that will replace only about 40% of their lost wages.

The UAW strike fund also covers some benefits such as medical and prescription drugs, but it does not cover benefits like dental and vision, among others, according to the union.

As the weeks continue, striking workers will inevitably feel more and more of the pinch. But Kyle Bendert, who has been on strike for nearly three weeks at the Ford assembly plant in Wayne, Michigan, said taking a temporary pay cut is worth it if workers eventually "get the contracts we deserve."

"It could have some damages to pay for both us and the company," Bendert said. "But whatever we got to do for us and for future generations of us."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))