Elizabeth "Ely" Rosales Aguilar has built Raíz Chocolate from her San Diego home kitchen, turning a childhood love of chocolate into a small but thriving business. She carefully sources Mexican cacao and crafts silky bars and rich drinking chocolates, like champurrado, using recipes passed down for generations. Her work is precise and deliberate, highlighting skill, patience and artistry while remaining deeply rooted in tradition.

From bean sourcing to finished bars, Ely keeps her process transparent and small-scale, with an emphasis on preserving natural flavors — a sharp contrast to mainstream chocolate production. The name Raíz, which means "source" or “root” in Spanish, reflects that commitment to honoring cacao’s origins and the heritage behind each recipe.

" [In Mexico's cacao farms] it's kind of like you want to pass on the knowledge to your family members of how to grow this plant — why is this plant important," Ely said. "It starts from there. Farmers that grow the cacao love the cacao because of what is attached to their family history. I wanted to be involved in, somehow, with the cacao world in my country. Even though I'm very close to the border, I do get homesick."

California's home kitchen and cottage food laws allowed her to turn that passion into a legitimate career, offering an alternative to mass-produced chocolate. Her story blends resilience, entrepreneurship and cultural heritage, showing how craft, intention and tradition can transform a home kitchen into a business that delivers exceptional flavor while preserving the legacy of Mexican chocolate-making.

Guests:

- Elizabeth "Ely" Rosales Aguilar, Raíz Chocolate founder

Sources:

- Home Kitchen Operations: Microenterprise Home Kitchen Operations (MEHKO) and Cottage Food Operations (CFO) (SanDiegoCounty.gov)

- California Cottage Food Operations (University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources)

- Microenterprise Home Kitchen Operations (California Department of Health)

- Restaurant Owner Demographics (National Restaurant Association)

- At-home businesses are growing. Women and people of color benefit the most (Chabeli Carrazana, The 19th, 2021)

- Almendra Blanca Bar - 70% Single-Origin, Finca Frida, México (Raíz Chocolate)

- Revival Cacao (Supplier for Raíz Chocolate)

- ILAB Cocoa Storyboard: Exposing Exploitation in Global Supply Chains (U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of International Labor Affairs)

- Mars Supply Chain Transparency (Mars)

- In Maya society, cacao use was for everyone, not just royals (Richard Kemeny, ScienceNews, 2022)

- Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica: The Aztecs and the Maya; Where did the Ritual Use of Cacao Originate? (Caroline Seawright, 2012)

- The Maya civilization used chocolate as money (Joshua Rapp Learn, Science, 2018)

- What is the chocolate and cocoa industry worth in Mexico? (Laura Islas, Merca 2.0, 2025)

- Mexico cocoa bean imports and exports (World Integrated Trade Solution)

- Cottage Foods and Home Kitchens: 2021 State Policy Trends (The Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic, 2022)

Episode 28: Raíz Chocolate Transcript

Elizabeth "Ely" Rosales Aguilar: Do you want, do you want to try it now? Would you want to have a small sip or not? It doesn't take too long.

Anthony Wallace: OK.

Rosales Aguilar: Yeah.

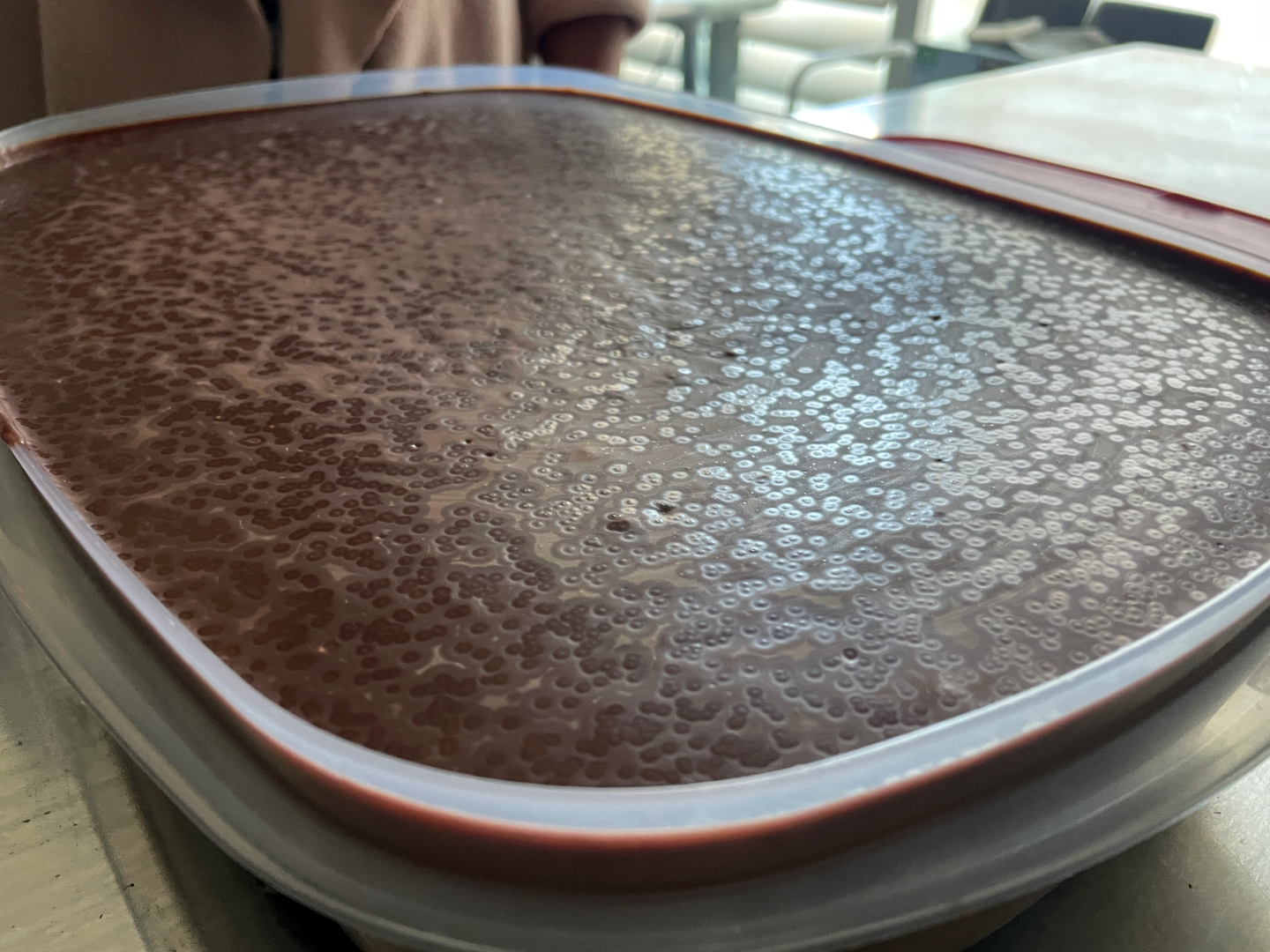

Julia Dixon Evans: Producer Anthony and I are in Ely's home kitchen about to try her famous champurrado.

So this is a mixture of chocolate, spices and corn, basically.

Wallace: This is so good – I love it.

Rosales Aguilar: It’s very hot.

Wallace: It's really hot.

Evans: It's a little thick from the corn. Not too sweet. A rich spiced chocolate with hints of cinnamon. A recipe passed down through the generations.

Rosales Aguilar: Champurrado, it's a warm, cozy drink that you share with your family at home when everyone is together, when you want a little bit of like, oh, I need a little love.

Evans: We're in her kitchen because it also happens to be the headquarters of a local business, one that started, at least partly, from a moment of exasperation. In 2019, Ely couldn't find a job. She'd recently moved to the United States from Tijuana and was newly married. She had a strong career in marketing in Mexico, but struggled to start a new life in the U.S.

Rosales Aguilar: It's really hard to get a job in San Diego if you are coming from another country. Even though you have your degree, even though you have the experience, it's difficult.

Evans: She was working in a preschool to get by, but in her free time, she was rediscovering a passion from her childhood and cultural heritage.

Rosales Aguilar: I fell in love with the process of chocolate making.

Evans: Around that same time, California's laws were evolving, opening the door for a different kind of business. Suddenly a new possibility emerged.

Rosales Aguilar: I was really amazed. I was like, what? You can do this at home? Are you kidding me?

Evans: Ely went all in, researching, testing recipes, making chocolate in her home kitchen and selling it at markets. It was a hit, and the project felt like it could be sustainable.

Rosales Aguilar: I worked in a preschool for one year, and in two events I got half of the year's salary in just two weekends.

Evans: That's amazing.

Rosales Aguilar: And that is crazy.

Evans: Ely's experiment turned into the job she was looking for, but just a few years ago, her chocolate business would've been illegal. Today, we go inside a real cottage food business to explore how it could challenge a massive, shadowy chocolate industry, and we taste the centuries-old traditions this home kitchen is bringing back.

Rosales Aguilar: My name is Elizabeth Rosales Aguilar. My company name is Raíz Chocolate. I make chocolate with Mexican inspired recipes

Evans: From KPBS Public Media, this is The Finest, a podcast about the people, art and movements redefining culture in San Diego. I'm Julia Dixon Evans.

[Theme Music]

Evans: Before 2013, if you wanted to start a food business, you had to buy or rent a commercial kitchen. The startup costs were huge. Over the past decade, California and San Diego County have passed laws that allow people to sell food they make at home. These are Cottage Food and Microenterprise Home Kitchen Operation laws.

Rosales Aguilar: It is good that they opened this, the possibility of running a business from your home.

Evans: These laws have dramatically lowered the barrier to entry for food businesses. Early reports show that compared with conventional food businesses, a much larger portion of home kitchens are owned and run by women and people of color.

Ely and her chocolate brand focus on a distinct, traditional and really tasty approach to Mexican chocolate making. And it's with her drinking chocolates that Ely really gets passionate about her work's connection to tradition.

Rosales Aguilar: Because in Mexico, chocolate is consumed mostly in drinks. My goal would be to make chocolate drinking mixes that are adapted to the modern kitchen so that people can easily prepare them at home.

Evans: I first met Ely in November at an artisan holiday market at the Mission Trails Visitor Center. She was selling chocolate bars, chocolate-dipped candied orange slices and, of course, a variety of drinking chocolates, like the champurrado. I was struck by how knowledgeable she was about cacao – not just chocolate production, but growing practices, history and even the big stuff, like climate change. I sampled one of her Almendra Blanca bars and was immediately hooked, and I noticed a note on the packaging: ‘Made in a Home Kitchen.’ A required note like that can feel like a warning label, but for Ely, it was more like a beacon. This chocolate was made with love. Still, we were curious. She made all of this at home? We wanted to know more.

Rosales Aguilar: Hi.

Wallace: Hello.

Evans: Hello.

Rosales Aguilar: Come on in.

Evans: This is Anthony.

Rosales Aguilar: Hi, Anthony. Nice to meet you.

Wallace: Nice to meet you.

Rosales Aguilar: Hey, can I bother you really quick with this one's? We are only indoor shoes.

Wallace: OK, no problem.

Rosales Aguilar: Thank you so much.

Evans: Ely lives in a quiet neighborhood in the shadow of our local mountains. From the outside, her house seems just like any other on the cul-de-sac. And inside, the entryway leads us to a welcoming living room with tall windows overlooking the sunny backyard. Ely has a separate clean room elsewhere in the house, but first she shows us the kitchen. Here is where she makes her morning coffee and prepares food for her young family. Magnets on the fridge look just like anyone else's. And she's able to do some of the chocolate work here in a dedicated storage and prep nook where most might put their kitchen table. She opens up a large storage bin full of cacao beans.

So this is unprocessed right now?

Rosales Aguilar: Yes.

Evans: OK.

Rosales Aguilar: This is a process.

Wallace: Yeah. I can smell it.

Rosales Aguilar: Yep.

Evans: These beans are the first step in the process.

Rosales Aguilar: Do you want to eat one?

Wallace: Yeah. I'll try one.

Evans: Yes, sure.

Evans: Ely cracks some of them open for us to try, like a cacao nib.

I really like it.

Wallace: It’s good.

Rosales Aguilar: This is the way we get them directly from the farms.

Evans: These are Ely's workhorse beans that go into most of her bars and some drinks, called Almendra Blanca. It's a special bean that's white inside when it's picked off the tree. It's very specific to one region in Mexico.

Rosales Aguilar: These ones are from Chiapas.

Wallace: OK.

Rosales Aguilar: Yes. These are from a farm called Finca Frida, and they're in the Southern, very, very close to Guatemala.

Wallace: OK.

Evans: Ely works with smaller farms that have an open door policy, open to visitors. She knows where her beans are coming from and trusts the farmers that grow them. This kind of transparency is not at all the norm in the mainstream chocolate industry.

In fact, Mars, the company that makes Snickers and Three Musketeers bars can only trace back half the cacao it purchases to the farm it came from, and that opacity hides some ugliness. Sixty-percent of the world's cacao beans come from Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana in West Africa. More than 1.5 million children work on cacao farms there doing dangerous work.

And in the last 65 years, chocolate production has obliterated 90% of the rainforests in Côte d'Ivoire. It's a shady, massive industry — a product of modern international supply chains.

At cacao farms in Mexico, Ely said she'll see children playing or helping their parents, but there it's not about feeding a global industry. It's about preserving a millennia-old tradition that stretches back to the time of the Mayans.

Rosales Aguilar: Over here it's kind of like you want to pass on the knowledge to your family members of how to grow this plant — why is this plant important. It starts from there. Farmers that grow the cacao love the cacao because of what is attached to their family history.

Evans: Ely's working outside that big, ethically questionable chocolate machine. She's doing things a more old fashioned way — smaller farms, traditional recipes. For her, it's personal.

Rosales Aguilar: I wanted to be involved in somehow with the cacao world in my country.

Evans: Ely grew up in Tijuana and has her own family history with chocolate, especially in the form of champurrado, the spiced chocolate drink we tried earlier.

Rosales Aguilar: My grandma used to make tamales every winter. And kind of like our pay for doing the tamales was to have champurrado. Yeah. I remember just sitting in her living room watching a telenovela and eating a tamale and champurrado.

Evans: Mexico is the birthplace of chocolate, and it was a central part of Indigenous cultures there before colonization. It was sacred, used in spiritual ceremonies and even as a form of currency. But globalized mass chocolate production threatens to gobble up that whole tradition. Thanks to those cheap beans from Africa, Mexico now imports more cacao beans than it exports, and Ely's afraid people, even in Mexico, are forgetting the traditional recipes. They're more familiar with Hershey's. She says when they want something upscale, they don't think of Mexican chocolate.

Rosales Aguilar: One of the teachers that I studied with, he's an anthropologist and all his work is around cacao, and he said it’s sad, but us Mexicans, in a way, have the palate very colonized. They would pay extra money to say, oh, sip this European chocolate, and they take it as high quality just because you add the word European, but you are missing like all of this amazing recipe. Come on, there are recipes that are made with flowers that are so fragrant. And the tree is unique to a very small town called Huayapam. And there is a guy that's 80 years old that manually goes on top of the tree to harvest every single flower to make tejate and you don't call that fancy? Like why not? And you call that, and that's not important? Like why?

Evans: Ely's passion, really what would become her mission, is what drives every step of her work.

Rosales Aguilar: When we started the company, I was sourcing cacao from India, from Guatemala, from Brazil, and making all of these different type of origins. And then I was thinking, yes, I like it, but it's not, that's not what where my heart is. I don't know how it's grown in there. And I thought, why am I trying so hard to get into this new wave of like chocolate makers?

Evans: She realized she didn't need to search outside of her own tradition.

Rosales Aguilar: It's like I have my own and it is very strong and I love it, and I would love the world to know it.

Evans: Ely's Almendra Blanca bar is 70% dark chocolate. It has a delicate flavor with hints of caramel and a little fruitiness, but still a smooth warmth. I recently gifted one to a friend who later texted me, quote, this may be the best chocolate I've ever had. It has the delicious flavor of the land where it was grown. The terroir wine lovers talk about. The same land where beans have been grown for thousands of years. This is something that's almost totally lost in industrial chocolate production. Those big companies like Mars and Hershey's blend beans from many different places and farms. They often add alkaline salts to reduce acidity and try to make every bar taste the same.

But Ely's operation looks a lot different. After the break, we'll learn how the flavors of the Almendra Blanca cacao bean come to life in a silky, smooth bar, with the help of some unconventional tools and a lot of determination. Stay with us.

[Music]

Evans: The beans are fermented on the farm. The rest of the process is up to Ely. For these first steps, we're still in Ely's kitchen. First step is roasting.

Rosales Aguilar: So the roasting happens here. It's a very small roaster. This is a coffee roaster, usually for half a pound to one pound of coffee.

Evans: Then she scoops them into the juicer that she uses to crack up the beans.

Rosales Aguilar: OK, ready?

Evans: Yes.

A lot of her equipment is not originally meant for chocolate production, just affordable kitchen gear that gets the job done. She's resourceful, always ready to adapt to challenges. She's been like that her whole life. One thing you notice about Ely right when you meet her is that she has one hand, but you also forget this just as quickly. It doesn't seem to change how she operates.

Rosales Aguilar: I was born with one hand only. So I have adapted pretty nicely, I think, and I can do everything on my own. I've had a couple of situations where people have approached me in the markets and said like, oh, I saw this little kid in a pool that only had one hand as well, and he was also very lively and very like non, didn't make a big deal about it and stuff like that, and I thought, wow. They have a preconception of like, oh yeah, because you should be like maybe very sad or you have problems or something like that. But I am fortunate that I was raised by parents that didn't make a big deal about it. They used to bring me to the Shriners Hospital in Los Angeles every year, and they would every single year offer me a prosthetic hand. And every single year I would say, no thank you. You can offer it to a kid that needs it. At the moment, I didn't understand, but now as an adult, I was like, yeah, good answer. Good job, mom and dad. Yeah.

Evans: Being agile and resilient is pretty essential in a home kitchen. The whole movement has had to overcome some pretty intense resistance, but over the years, these hardworking chefs have proven that their products and production methods are as safe as those in commercial kitchens. And at Ely's, everything's up to home kitchen code. Inspectors come every year, and Ely approaches it with her characteristic positivity.

Rosales Aguilar: No, I like it actually, because every time that they come, they're always very helpful. I don't know. They have so many good suggestions. They're always very helpful.

Evans: Following the rules, we washed our hands and dawned hairnets as we entered the most chocolate factory-like room in the house.

Oh, wow.

Wallace: It smells good in here.

Evans: It does smell good.

This room is small. A front room just off the main entrance. It would probably be used as an office in anyone else's home. It's dark and cool inside, with blinds drawn and carefully monitored climate and humidity equipment humming softly. Along one wall are two unusual machines. One is basically a chocolate faucet, and the other looks almost like a giant cauldron.

Rosales Aguilar: So this machine is the grinder.

Evans: Into the grinder goes cocoa butter, sugar and the roasted, cracked and shelled cacao beans. For the drinking chocolate, she adds some spices.

Rosales Aguilar: This one runs for about three days.

Evans: Out of that machine comes a mass of already delicious, but crumbly chocolate. For drinks and champurrado, that's perfectly fine, but right now she's making bars and the bars need that crisp, smooth texture, which entails another very important step after grinding.

Rosales Aguilar: And this is a tempering machine. This is what it does, it gets hot.

Evans: The tempering machine is the chocolate faucet. It gradually warms and cycles the chocolate until it reaches the perfect texture and temperature. Exactly when to stop grinding and tempering, those are intricacies Ely learned through trial and error.

Rosales Aguilar: We still need a little bit more because it does, one degree does matter.

Evans: Though she had to do a ton of research and practice, Ely has actually been learning to make chocolate her whole life.

Rosales Aguilar: I've always wanted to work with chocolate or know how to do it. And when I was growing up, I used to tell my mom, Ama, how like, let's make some chocolate. And my mom used to get me tiny pieces of the blocks that she would buy for her desserts and teach me how to temper it, basically. And I used to make them for my friends or whatever. No, I got very excited. Then we went to Oaxaca because I always used to ask, Ma, but how does, how is chocolate made? And we saw the women working with chocolate and said, oh, that's how, and then just life happened.

Evans: Ely studied visual arts and got into editorial photography. She had a successful career in Mexico City before moving back to the border region. When she met her husband, she felt the spark of chocolate making again in the form of a challenge.

Rosales Aguilar: So my husband and I met here in San Diego scuba diving, and we started dating and he's from Indian origin and vegetarian.

And so he started showing off his cooking skills and cooking a bunch of very delicious dishes. So then I said, wait a minute. Mexican food is also very tasty. But then I thought, he's vegetarian so I cannot cook anything. So then I said, OK, what can I make that is Mexican? What can I make? Then I thought, OK, chocolate. So he had tried chocolate. Didn't like, didn't think it was special or anything. I was like, I'll show you. So that's how it started, yeah.

Evans: She got some cacao nibs at Sprouts.

Rosales Aguilar: I did have one of those, to make salsa, a mortar and pestle of the volcanic rock. So I said, this one will work. So I just started adding everything and then my husband got excited, oh, let's add some lavender. OK, sure. Let's sweeten it with dates. OK. So we made some little truffles and yeah, I surprised him.

Evans: Like, did you impress him?

Rosales Aguilar: Obviously, yes. After that he, here's your ring.

Evans: She started tinkering with recipes in her kitchen and decided to dive in full-time. From the start, there were obstacles, two years to get permits, buying equipment and figuring out space. She's still always perfecting things. Fixing bottlenecks in production is an ongoing process.

Rosales Aguilar: You have to really count your pennies and say, OK,

I want to grow in this. OK. Yeah, we don't know, like I don't know how to run a business. I'm just learning through it.

Evans: One of the many challenges is farmers markets. They have such long wait lists, so Ely sells mostly at special events. You can find her schedule on Instagram. Her customers are dedicated and the drinks she's passionate about are her most popular products.

Rosales Aguilar: From the very beginning, we have had customers that follow us around wherever we are.

Evans: It's going so well that she can hardly make enough chocolate.

Rosales Aguilar: You're doing good, but then you are starting to have more demand than what you can produce. I would like to hire someone so that that can free up my time so that I can have the website running again, because right now I have everything as sold out.

Evans: Keeping up with demand is physically intense. Favoring one side as she works has caused back problems.

Rosales Aguilar: The chocolate blocks, those are hard to break. I started with an ice pick, but then I have this part, like right part of my back, my hand goes numb in the night.

Evans: And it's time consuming. After the tempering process, Ely pours the chocolate into custom molds, which adds an intricate floral pattern on the face of the bar. It all has to be done on a tight timeline to get the quality she wants.

Rosales Aguilar: Today I really have to finish molding this. Right. And I know. So I will sleep after I am done with that. So right now the production can extend all the way to 2 a.m.

Evans: We've set you back a little bit?

Rosales Aguilar: No, no, no. This is fine. No, it's fine.

Wallace: Do you go till 2 a.m. like frequently? Is that normal?

Rosales Aguilar: Sometimes, yes. That's pretty common. Yeah.

Evans: Ely's world changed again recently. She just became a mom. Juggling production around her baby's nap schedule, balancing long work days and sleepless nights. For Ely, it's another challenge, but at home, her family can share in the experience.

Rosales Aguilar: It’s been, oh, I'm gonna get emotional because it's been very hard. Yeah, it's been really tough to balance things. No, but the other day, the other day, my daughter, after spending like the whole day in the kitchen. She saw the final packaging of things and she just looked at them and said, wow. Oh my God, that made my day. My entire exhaustion of the day. Everything like it was amazing. And then my husband came down from the stairs and she just pointed at the things and told him, Baba, Baba, Mama, wow. Oh my goodness. It was the best feeling. It was the best feeling.

Evans: Raíz and so many other businesses run by mothers and other people who need flexibility or who can't pull off a huge initial investment, these would not exist without recent home kitchens and cottage food legislation, and these businesses challenge the status quo of our food system. Those laws gave Ely opportunities she couldn't have had otherwise. With Raíz, she not only makes money for her family, she rediscovered her childhood passion for chocolate and found purpose in it. Ely's business exists in direct contrast to the mainstream chocolate industry. Every step, from bean to bar, is visible, simple and designed to celebrate the natural deliciousness of Mexican chocolate. And even through hard work and late nighs, Ely hasn't lost the love and passion that Raíz Chocolate is built on.

Do you ever feel like after a long day, or after a long period, working, do you ever feel like, ugh, I don't want to taste another piece of chocolate?

Rosales Aguilar: It hasn't yet reached that point, I think. Yeah, it's always exciting to either eat my own chocolate or to try someone else's creation. Yeah. I think it's always a joy.

[Music]

Evans: A special thank you to Elizabeth Rosales Aguilar for her help with this episode. And thank you so much for listening. If this episode resonated with you, please subscribe. Leave a rating or comment. It makes a real difference and helps stories like these reach more people. Also, we print them out and read them out loud at our desks.

We're off next week, but in two weeks on The Finest, the story of Chula Vista's own Jessica Sanchez. Catapulted to fame on “America's Got Talent” at a young age, Jessica returned to the show last year to try to win it all. In the decades between, she experienced some of the highest highs and lowest lows in the music industry and came back home to find purpose.

Jessica Sanchez: Being 10 years old and being 16 years old on these big stages, you're like, all you see is the spotlight and you're like, oh my gosh, I can win Grammys and go and do tours and sell out stadiums. And I think I lost, I lost the feeling of why I was doing this.

Evans: I'm your host, Julia Dixon Evans. Our producer, lead writer and composer is Anthony Wallace. Our engineer is Ben Redlawsk, and our editor is Chrissy Nguyen.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

From KPBS Public Media, The Finest is a podcast about the people, art and movements redefining culture in San Diego. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts or click the play button at the top of this page and subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, Pocket Casts, Pandora, YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

Have feedback or a story idea? We'd love to hear from you. Email us at thefinest@kpbs.org and let us know what you think.