The Noir Book of the Month Club officially launches with Dashiell Hammett's "The Maltese Falcon" and a guest blog by D.A. Kolodenko. Give the blog and the book a read before joining KPBS Cinema Junkie Beth Accomando for the film adaptation of "The Maltese Falcon" on Jan. 28 as part of the Film Geeks SD new series Noir on the Boulevard.

Raymond Chandler wrote: "Hammett was spare, hard-boiled, but he did over and over what only the best writers can ever do. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before."

The black bird

In 2013, a 45-pound, lead statuette of a falcon perched on a simple base sold at Bonham’s auction house in New York City for $4.1 million. Reported to be one of at least two existing falcons made as props for John Huston’s 1941 Warner Brothers' film version of Dashiell Hammett’s acclaimed 1930 novel, "The Maltese Falcon," the bird was purchased by Las Vegas hotel magnate Steve Wynn; it was among the highest prices ever paid for a movie prop. But the authenticity of the bird came into question, particularly after Bryan Borrough’s intriguing but inconclusive 2016 investigation in Vanity Fair. Had there been as many as a half dozen Maltese Falcons created for the film? Were they made of lead or plaster? Who owns the real Maltese Falcon(s)?

But even Wynn’s bird is not the most valuable: in 1994, famed New York jeweler Ronald Winston purchased another 45-pound lead falcon purported to be an original, which had been given to actor William Conrad in the 1960s by Jack Warner himself.

Winston used this falcon as the model for his creation of a Maltese Falcon that would rival the one of legend in the film. Made of 10 pounds of gold with ruby eyes and a 42-carat diamond dangling from its beak, Winston’s falcon cost $8 million to make, and was sold to an unidentified buyer for an undisclosed price. And who knows where it is now.

That so much value and mystery has accrued around these manifestations of what was 88 years ago a fictional bird statue at the center of a serialized story in a pulp detective magazine is a testament to the persistent power of Hammett’s story and its artful realization a decade later in Huston’s film.

Dashiell Hammett

Hammett wasn’t a writer from the get-go. Born in Maryland in 1894, he was a school dropout at the age of 13, and then a factotum helping support his family in odd jobs around Baltimore and Philadelphia, and wound up at the famous Pinkerton Detective Agency in 1915 when he was 20 years old.

Hammett worked for Pinkerton’s in San Francisco and then joined the army, where he caught tuberculosis, which weakened him for life. In the army, he met a nurse — they’d soon be married with two kids. But because of his illness, he could no longer hack it as a detective, so he began to turn his Pinkerton’s experiences into fiction, writing more than 80 short stories and (just) five novels over the course of his life.

Hammet’s first detective, the never-named Continental Op, was the first of his kind: a hardboiled, unsentimental, no-nonsense tough guy who solved crimes methodically, whose status as a company man for the Continental Detective Agency mirrored Hammett’s own five years in the business. The unsentimental protagonist in the vast majority of Hammett’s stories, the OP was short, heavyset, middle-aged, jaded and based on a detective that Hammett worked with.

Much of what became the character of "The Maltese Falcon’s" Sam Spade was present in the Op — what Thrilling Detective magazine described as “the terse tone, the casual violence, the cold, methodical professional[ism], the cool pragmatism wrapped around a code of honor he would live — or die — for.”

But although Spade, who came along years after the Continental Op, had all the toughness and cynicism of the OP, he was a more idealized character. Spade was independent, his own boss. He was younger, tall, strong and devilishly handsome. Still hard-boiled and cynical, but sexier and more romantic a figure, Spade was created specifically for Hammet’s third novel, "The Maltese Falcon," the only full–length novel in which he appeared (he also shows up in four short stories). Hammett explained:

Spade has no original. He is a dream man in the sense that he is what most of the private detectives I worked with would like to have been and in their cockier moments thought they approached. For your private detective does not — or did not 10 years ago when he was my colleague — want to be an erudite solver of riddles in the Sherlock Holmes manner; he wants to be a hard and shifty fellow, able to take care of himself in any situation, able to get the best of anybody he comes in contact with, whether criminal, innocent by-stander or client.

Spade became the prototype of the hard-boiled detective for all subsequent crime fiction and film noir. But "The Maltese Falcon" had so many of the other elements already in place, too: the colloquial dialogue, the femme fatale, the unsavory side of life in the big city, a labyrinthine plot in which flawed characters unravel as it unfolds and the pervading, bleak, fatalistic perspective that gives noir its dark underpinnings.

Raymond Chandler, Elmore Leonard, James Ellroy, Walter Mosley, Sue Grafton, Ridley Scott, The Coen Brothers — anyone who has taken on the hard-boiled detective genre owes Hammett a toast of “Success to crime” (Spade’s toast to the cops in "The Maltese Falcon" over wine glasses full of Bacardi).

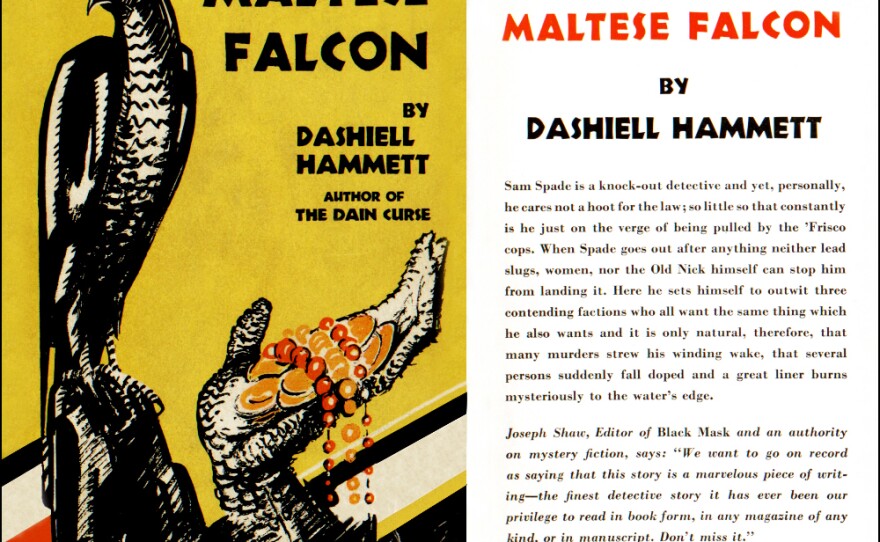

"The Maltese Falcon" was originally published in Black Mask Detective magazine, serialized in five parts in the September 1929 to January 1930 issues. Knopf published it in novel form in 1930, and it was a hit, with seven printings that first year, and was — unheard of for a detective novel — taken seriously by the literati, with Hammett now hanging out with literary luminaries like Ernest Hemingway, Dorothy Parker and playwright Lillian Hellman, with whom he began an enduring affair.

The novel

The idea of this blog is that you’re reading the novel along with me, so even though it’s an 88-year-old story that you likely know by now, I'm going to talk about elements of the story without giving away too much— you’ve been duly warned.

What happens is a gaggle of greedy characters fight each other talon to talon for a treasure that may or may not exist. Spade gets pulled in when an alluring woman who operates under multiple names — “Brigid O’Shaughnessy” supposedly being the real one — hires him and his partner to help find her sister. Things don’t go as planned, and Spade endeavors to do whatever it takes to find out what’s driving this mysterious woman, and what led to his need to scratch his partner’s name off of his office’s frosted glass door panel.

What I’d like to ask you to consider while reading the novel are two questions:

- Whether Spade loves O’Shaughnessy. There’s some debate about this, and I’ll tell you where I stand on it in the next blog after you’ve seen the picture (for what I assume is at least the third time).

- What the heck is the point of Spade’s telling O’Shaughnessy the story about the Flitcraft case? It’s even become known in literary circles as the “Flitcraft parable.” I don’t think it’s a parable; I think Hammett just liked the story and wanted to tell it. But it has to mean something doesn’t it? Hint: Hammett liked to use the word “meaningless” a lot. We’ll briefly revisit this question next time, too.

John Huston’s film version of "The Maltese Falcon" — made a decade after the publication of the novel — was his first directorial effort. Son of the famous actor Walter Huston, and already a successful screenwriter, Huston wanted to direct, and was given the chance by Warner Brothers on the condition that the next film they produced from one of his screenplays was a success; that film turned out to be "High Sierra," a box office hit. It also brought Huston’s friend, bit player Humphrey Bogart, to prominence. Warners kept their word, and Huston cast Bogart in "Falcon." The film made "Bogie" famous.

Huston also cast his girlfriend, Mary Astor, as O’Shaughnessy. (Confession: Based on how she reads in the book, I’d have preferred Joan Bennett. Who would you have cast?)

The film also makes great use of Peter Lorre as the gay, Middle-Eastern dandy, Joel Cairo, B-movie helper Elisha Cook Jr. as his young thug boyfriend, and introduces the great Sydney Greenstreet in his first film role as the larger-than-life, stop-at-nothing connoisseur of the finer things, Kasper Gutman.

Hammett’s unflattering portrayals of masculinity, femininity, homosexuality, of the Levantine, of cops — of pretty much everybody in the lower depths and everything they do — are toned down in the film, as it was made under the Hays Production Code established by the film studios themselves to get the morality police off their backs in the mid-1930s.

But even without, for example, the scene in the novel where Spade persuades O’Shaughnessy to strip naked so he can search her for a missing $1,000, Huston sticks close to the novel — it was great, and he intended to bring it to life rather than take too many liberties in adapting it. Of course, he did make it his own through meticulously planned camerawork and a few tweaks and additions, including adding Spade’s famous Shakespearesque description of the Maltese Falcon as “the stuff that dreams are made of.”

See you at Digital Gym Cinema on Jan. 28 — looking forward to hearing about your experience with "The Maltese Falcon."

D.A. Kolodenko: Musician. Waiter. Warehouse worker. Print shop manager. College professor. Lecturer. Columnist. Journalist. Editor. Science writer. Advertising copywriter. These are some of the things I’ve been. Detective. Hitman. Embezzler. Boxer. Prison inmate. Fugitive who escapes by running into a tunnel or climbing up something. These are some of the things that the books and movies I like have taught me to avoid being.