After more than 30 years in dark concrete storerooms in the bowels of the Civic Theater, where it was entombed by "hostile handlers," a major public work by Ellamarie and Jackson Woolley called "Reflective Sun" shines again as part of Mingei International's exhibition, San Diego's Craft Revolution: From Post-War Modern To California Design.

Drawn to art at an early age, Ellamarie Packard studied at San Diego State College in the 1930s and painted two murals on the campus that were commissioned with WPA funds. She was teaching art at the Francis Parker School where she met Jackson Woolley, who also taught there. Jackson had traveled to San Diego with a Shakespeare company to perform at the newly-built Old Globe Theater during the California Pacific International Exposition of 1935-36. He had studied acting, costume and stage design at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh and continued to act in and direct plays at the Globe while the Woolleys gained national attention for their enamels.

The Woolley's work won awards in prestigious exhibitions all over the country and became part of many major museum collections. They were active participants in the historic national gatherings of contemporary craft artists organized by the American Craftsmen's Council in conferences at Asilomar and Lake Geneva. But they were staunch modernists and even their most decorative work, animals, or figures in medieval costume, was rendered in the language of modern art; Picasso seems to have had the most obvious influence.

They were also tireless experimenters who went in surprising directions as they matured. For example, after years of using copper sheet strictly as a support medium which their designs and brightly colored enamels covered completely, they gradually came to exploit the copper itself as an sculptural medium, hammering and working its surface in a process called repousse. Their architectural compositions often used sections of shaped copper, that was not enameled, to add depth and contrast to the glassy, enameled areas. They also made numerous works in copper alone, or mostly of copper, like their 1964 commission for the Civic Theater in downtown San Diego.

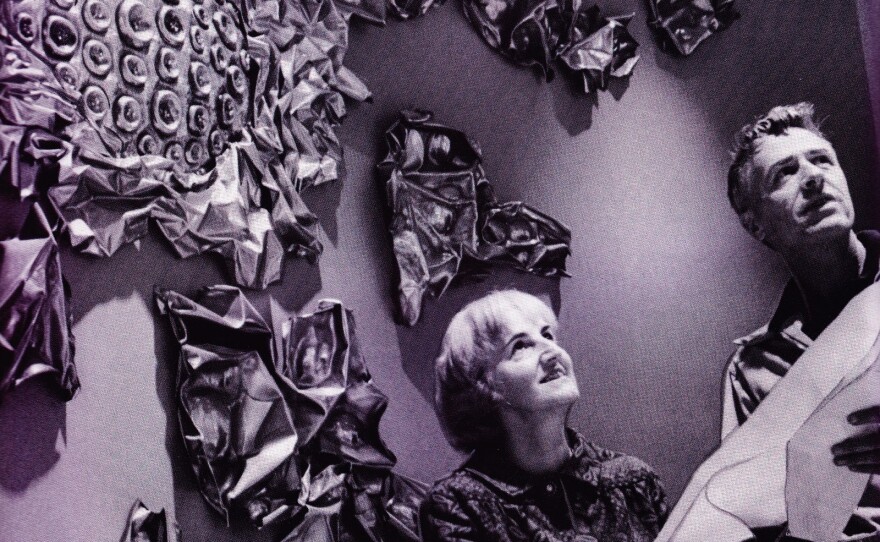

Modern architect Lloyd Ruocco, long a comrade of the Woolleys and an advocate for many local artists, had envisioned a modern theater for San Diego since the late 1940s. He finally got the chance to design the Civic Theater, completed in 1964, but had to collaborate with three other architects and compromise many of his ideas. The Woolleys were commissioned to make copper reliefs and wall ornamentation for the interior of the building. In the main auditorium, hundreds of pieces of crumpled copper were fashioned into light fixtures surrounding bulbs arranged in tall, vertical sections on both sides of the walls. As Jackson Woolley reportedly wrote, these were meant to warmly reflect the side-lights in folds of copper "especially when the house lights are dimmed and then quenched in that magic moment just before a performance." There were also two major wall reliefs, "Creative Sun" and "Reflective Sun," positioned at opposite ends of the lobby above the stairwells. While almost all of the work in the theater was made with nothing but shiny, bare copper, the centers of these two suns also involved some repousse and enamel colors.

The Civic Theater commission must have had particular significance for Jackson, given his background in theater and his convictions about public art. And this wasn't their first attempt to secure a local civic commission. In 1961, the Woolleys had designed a mural for the facade of the County Courthouse on Broadway that proved to be controversial and was rejected by the County Board of Supervisors in favor of a blank wall.

Ellamarie had died in 1976 and by 1979 Jackson couldn't stand it any longer. He wrote to the Civic Theater management saying: "For a long time I have avoided going to the Civic Theater because it was so painful for me to see the semidestruction and total neglect of the copper reliefs that my wife and I were commissioned to make when the theater was built... Perhaps I have the right to demand, rather than recommend, the removal of the copper work, since attrition and neglect have reduced it to a visual libel on my late wife and me."

Architecture critic James Britton published excerpts from Jackson's letter in a story for the San Diego Union in September, 1979. Britton also said that when Jackson wrote his letter, there was already a plan underway to remove the Woolley's copper work and possibly auction it off to raise funds for re-decorating. Britton predicted that the work, including the two "Sun" reliefs—that had fared comparatively well, but had never been adequately lit—would go into storage where they would await "possible new life elsewhere." Way back in 79', Britton said that he hoped "the most studied compositions," "Reflective Sun" and "Creative Sun," "would beam again from public walls."

Many of the copper pieces used in the auditorium were sold through the City Store in Horton Plaza, but the two "Sun" compositions have been awaiting their uncertain fate for the last thirty years. In April the City of San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture, took possession of "Reflective Sun" and "Creative Sun." The energetic Dana Springs, who manages the Commission's Public Art Program, has set about cataloguing and accessioning the works. This arrangement between the theater and the commission was a saving grace that will ensure that these important examples of public art will be preserved and hopefully visible.

Dave Hampton is a frequent contributor to Culture Lust. He is the curator of "San Diego's Craft Revolution: From Post-War Modern To California Design" at the Mingei Museum in Balboa Park.